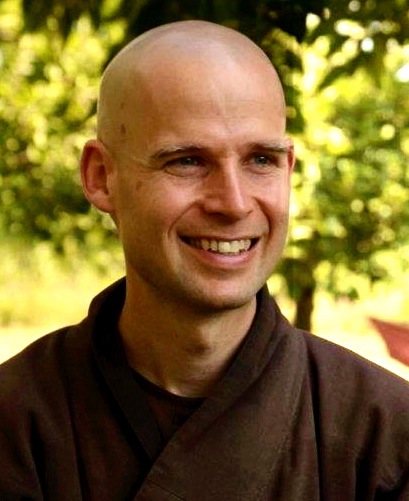

In celebration of Vesak, I chatted with Plum Village Brother Chân Pháp Lưu about the importance of the holiday, Engaged Buddhism, and the recent passing of beloved Zen Master Thich Nhat Hanh.

For those who are unfamiliar with Vesak, could you explain its importance to the Buddhist community? How will Deer Park Monastery be celebrating Vesak this year?

Brother Chân Pháp Lưu: On the full moon of May we celebrate the birth of Shakyamuni Buddha, our root teacher, by pouring water with ladles over a statue of a child. This comes from an early tradition—eloquently depicted by the poet Ashvagosha—that says streams of warm and cold water fell from the sky to bathe the just-born Siddhartha Gautama in Lumbini.

This symbolic act has a deeper meaning: within each of us is the nature of awakening; by caring for the baby Buddha we care as well for this awakened nature in each one of us and in those around us. Thay (Thich Nhat Hanh) reminded us to wash our plates and bowls with mindfulness after eating each day as if we are washing the baby Buddha. In this way Vesak becomes a skillful daily practice of watering the seeds of love and understanding in ourselves and others. Wouldn’t everyone wish to participate in the enlightenment of a Buddha?

How would you describe Engaged Buddhism to someone unfamiliar with the term? How has it evolved over the years since it first came to public consciousness?

Brother Chân Pháp Lưu: Engaged Buddhism means we see that our actions of body, speech, and mind have real effects on the world, and that by acting out of love and understanding we reduce violence and fear in the collective consciousness. The root of Engaged Buddhism is in our mind, and it radiates out into the world through our speech and bodily actions. For example, if we are aware of the seed of discrimination in our mind and take care of it there at the root, our speech and bodily actions naturally become more inclusive and accepting.

Concretely, it means that I let go of the idea that I am a separate self, cut off from the world around me, and see that my thoughts have real effects. I need to take care of how I nourish my thinking through sense impressions—through my eyes, ears, etc.—so that what I think, say, and do expresses compassion and understanding instead of blaming and judgment.

With this kind of mind training I experience less fear, and whether I am kind in my daily interactions to those I live with or whether I am locking myself to a tree to protest deforestation, I do so with love in my heart and not hatred. That is how I try to practice Engaged Buddhism. I do my best, but sometimes fail, and then try again. Patience and persistence in the practice are key. The experiences—positive or negative—of those around us in response to our actions are like a mirror to help us look at our own mind. Once you see that, it feels a bit silly to keep holding on to an idea of a separate self. Engaged Buddhism is one and the same with interbeing.

2022 has been a roller coaster ride of events in such a short span of time. One major event has been the war in Ukraine. How can we lean on the teachings and writings of Thich Nhat Hanh to help us be aware of the human cost of war and how we as individuals can feel empowered to dismantle the systems of oppression that make war possible?

Brother Chân Pháp Lưu: When we have an ethical foundation in our lives—what we express through our practice of the Five Mindfulness Trainings—we are contributing in a significant way to reducing the panic and fear in the collective consciousness that leads more and more countries into war. Though it is painful to see more weapons being produced all around as a response to the invasion of Ukraine, the real message has been the powerful collective wish of countries around the world to maintain peace. This is born from the wisdom of our ancestors; as Thay would say, the ancestors have already prepared everything. For every devastating act of destruction there are hundreds and thousands of acts of love and compassion.

The horrific war in Ukraine is in the news but the war in Yemen, just to mention one of many wars around the world, has been ongoing for years. Every day we need to practice to remember that war and violence—domestic violence, rape, and violence against those in the LGBTQ community—are ongoing. Most importantly there is the war that may be going on in our own heart. This is something we can act on right now. We can stop, breathe, and look deeply into that war to understand its roots. If we learn how to stop nourishing the war in our heart, we stop nourishing war in the world. That is what Thay called creating true peace.

There has been more and more discussion about the mental strain caused by COVID, unemployment, the climate crisis, and overall fear about the state of the world. What are some ways that individuals and communities can combat feelings of stress and helplessness associated with these events?

Brother Chân Pháp Lưu: Get out in nature! Put your hand on a tree and hold it there for twelve or thirteen breaths. Walk in silence together with someone you love for fifteen minutes. That someone you love can also be you! Too often when we feel overwhelmed by the situation in the world, we haven’t noticed how we’ve physically locked ourselves in the prison of our house or apartment. Go outside for no reason other than you like it. A house plant is feeble and needs extra care in ways a tree rooted outside in its native ground, planted by squirrels or jays, doesn’t. Make yourself a native tree through your mindful steps and breath. Mother Earth is there for you, in every cell of your body, but are you there for Mother Earth? It is not very helpful to combat feelings of any kind. Rather, just smile to them and see them as impermanent. Change the playlist of your thinking. That’s what going outside in nature for a mindful walk helps to do. We are a child of Mother Earth, and the trees, forest, and savanna are our native habitats. Any tree in a park can help us get in touch with the nature of our ancestors.

We would be remiss not to mention the recent passing of Zen Master Thich Nhat Hanh. When did you first meet Thay, and how has his passing affected you personally? What are your thoughts on his most enduring legacy?

Brother Chân Pháp Lưu: I met Thay first through his students—now my elder brothers and sisters. When I was 25, practicing meditation every day for almost a year, I was working part-time in a bookstore while living in the forest—like a forest monk—under a rock overhang above the town where I had graduated from university four years earlier. As an alumnus I had access to the library and was devouring anything I could find of Buddhist sutras and philosophy and was on track to go to Thailand to ordain as a monk.

One morning four monks came into the bookstore; it was like the monks in the sutras I’d been reading had stepped out of the book right into the store. The energy of the sangha was strong and inspiring. One of the monks invited me to a day of mindfulness at their new monastery in Vermont—Maple Forest. The nuns came by the next day and asked me where they could find a good Indian restaurant in town. A week or two later I rode my bike out on a Saturday evening, camping nearby, and met Sister Chan Duc and other monastics the following day. We listened to a newly recorded talk by Thay on how the community in Plum Village makes decisions with the help of a Caretaking Council.

The next time I came up, a nun invited me to stay for the family retreat they had started; a few days into the retreat I rode back to quit my job. After two weeks of retreat I hiked straight out from Maple Forest to wander through the backwoods of Vermont with my backpack, sitting in meditation with the help of a hanging bug net. I have always tried after that to spend time on my own after a retreat to digest what I had learned.

The following year, 2002, at the next family retreat, a sister let me know that Thay was coming on a tour and would speak in Providence, Rhode Island. I showed up to help set up for the public walk along the river, and one of the nuns offered me a sandwich and a ticket to the public talk that would follow. The monastics gathered on a stage outside and Thay suddenly appeared in the midst of the sea of brown robes. That was the first moment I saw my teacher. That night, when Thay spoke, I felt myself hanging on every word. I knew I didn’t have to go searching for a teacher anymore.

It is clear that Thay lives on through the sangha, through the clouds, the rain, and the sun. Thay had no doubt about this, and neither do I. Thay had little interest in making a fuss in keeping his body living on; I think it was mainly out of compassion for us that he did it for so long. We still tend to think that Thay is his body, no matter how often Thay told us that he is not limited by the body, and that is true for all of us as well. I see Thay very happy and free right now.

What was your path to monastic life?

Brother Chân Pháp Lưu: Suffering brought me to monastic life, especially the suffering that I caused to myself through my unskillful actions, through not cherishing the preciousness of my relationships. After eighteen years now as a monk, I see every day more clearly how 99% of my suffering comes from my own actions. This realization brings me a lot of happiness: I don’t feel like a victim anymore.

In my mid-twenties I felt driven, but I had lost faith in institutions, governments, even movements. Looking within with mindfulness at my body, feelings, mind, and at all phenomena, a joy manifested unlike any other I had experienced. I knew then that the path of a monk was the best way for me to generate this joy—and a lasting happiness—in this life, here and now.

Thank you Brother Chân Pháp Lưu for your time and insight, and to our readers, we are wishing you a meditative and peaceful Vesak.