By Richard Brady on

Dharma teacher Richard Brady reflects on how Lamp Transmission supported his healing and growth in freedom to share mindfulness with others in person and in his writing.

Ted, my therapist, writes a few words on a pad, then tears the sheet off. “Here’s your assignment, Richard.” I look down; on the first line he’s written freedom from.

By Richard Brady on

Dharma teacher Richard Brady reflects on how Lamp Transmission supported his healing and growth in freedom to share mindfulness with others in person and in his writing.

Ted, my therapist, writes a few words on a pad, then tears the sheet off. “Here’s your assignment, Richard.” I look down; on the first line he’s written freedom from. Halfway down the page he’s written freedom to. I suppress a sigh. Will this really lead me somewhere?

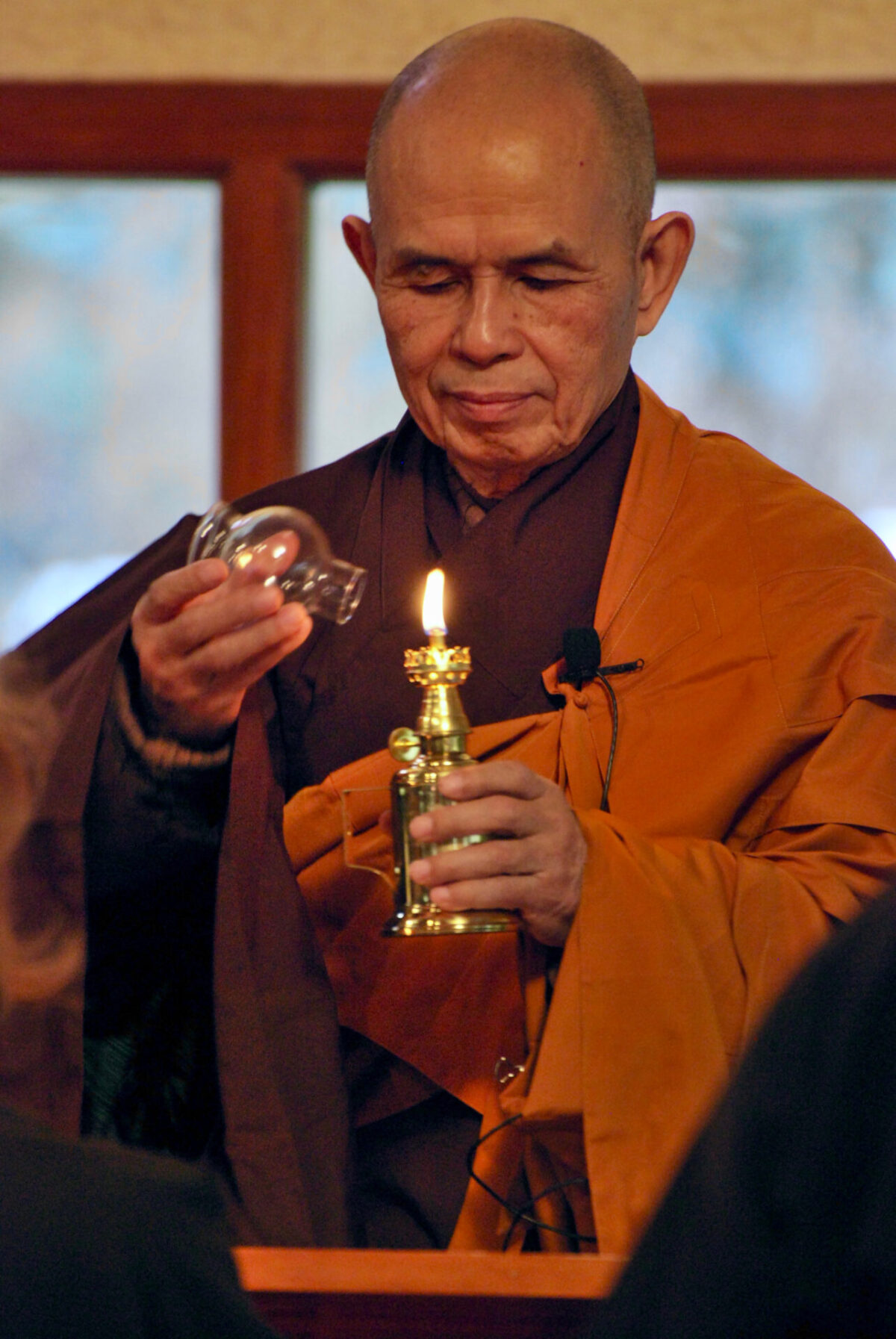

A few months earlier I received a message from Thích Nhất Hạnh inviting me to receive Dharma Lamp Transmission to become a Dharma teacher in his tradition. The ceremony would occur just before Christmas in Plum Village, France. I’m not a Dharma teacher, I think. I’m a math teacher. I have begun bringing mindfulness into my high school classes, hoping to help students learn this life skill that will increase their capacity to pay attention. I’ve also been leading mindfulness retreats for fellow educators. These are ways of sharing some of the precious gifts I’ve received from Thầy.

When I first heard this invitation might be coming, I felt excited, but I also began to worry about the expectations of others. I don’t want to travel around the country offering retreats and Days of Mindfulness like some Dharma teachers do. My focus is on sharing mindfulness with students and teachers. Perhaps I can call my friend Anh-Huong, Thầy’s niece, and ask her to discourage the invitation. But the invite arrives, and it’s too late for anyone to intervene. I’m surely not worthy of this honor, but I defer to Thầy’s wisdom, trusting that taking this step will help me grow. With that thought, I feel deeply and humbly grateful.

During the ceremony, I will be asked to present an “insight poem.” I’m not a poet. I’ve written poems for Elisabeth on her birthday and our anniversary, but an insight poem presented at a formal ceremony before Thầy and the Plum Village community? How could I possibly write that? The poem I write for Thầy is supposed to express insight about something. Hmm. What might that be? Remembering words from my study of Marshall Rosenberg’s nonviolent communication, I ask myself, What is alive in me? What is my vision? Since reading Thomas Wolfe in high school, I’ve been drawn to people who seem to be free: Henry Miller, Ram Dass, the Grateful Dead, Thích Nhất Hạnh. Do I have my own vision of freedom?

I’ve been reading alternative education texts and incorporating new methods into my math teaching, yet moments of true freedom in my personal life are rare. Unresolved issues dating back to childhood plague my relationships, including with myself. I’d like to learn something fresh about freedom that might inspire me. So, I begin discussing this with friends. No insight appears. Finally, a month before the ceremony in Plum Village, I raise my questions with Ted. “What does freedom mean? Where have I found freedom in my life? Where should I be looking?” Twenty minutes into the session, Ted interrupts me to ask how I am. Confused, I reply, “I’ve been telling you how I am for the last twenty minutes!”

“No, you haven’t,” he says. “You’ve been telling me about your family, your school, and your spiritual community. How are you?”

I realize I don’t know how I am. My habit is to look outside myself to find out how I am. Thoughts and feelings about others obscure my connection to myself and to my feeling free. At the end of our conversation, Ted hands me the paper with the assignment. During the days that follow, I write responses for both categories: freedom from and freedom to. Nothing new shows up. Disappointed, I report my results to him at our next meeting. Taking in my disappointment, Ted listens, remaining present with me.

I wake up a few days later with a fresh understanding. I see that my knots—my habit energies—are a part of me and that untying them is not a prerequisite for freedom. This revelation manifests as the poem I respectfully offer at my Lamp Transmission ceremony:

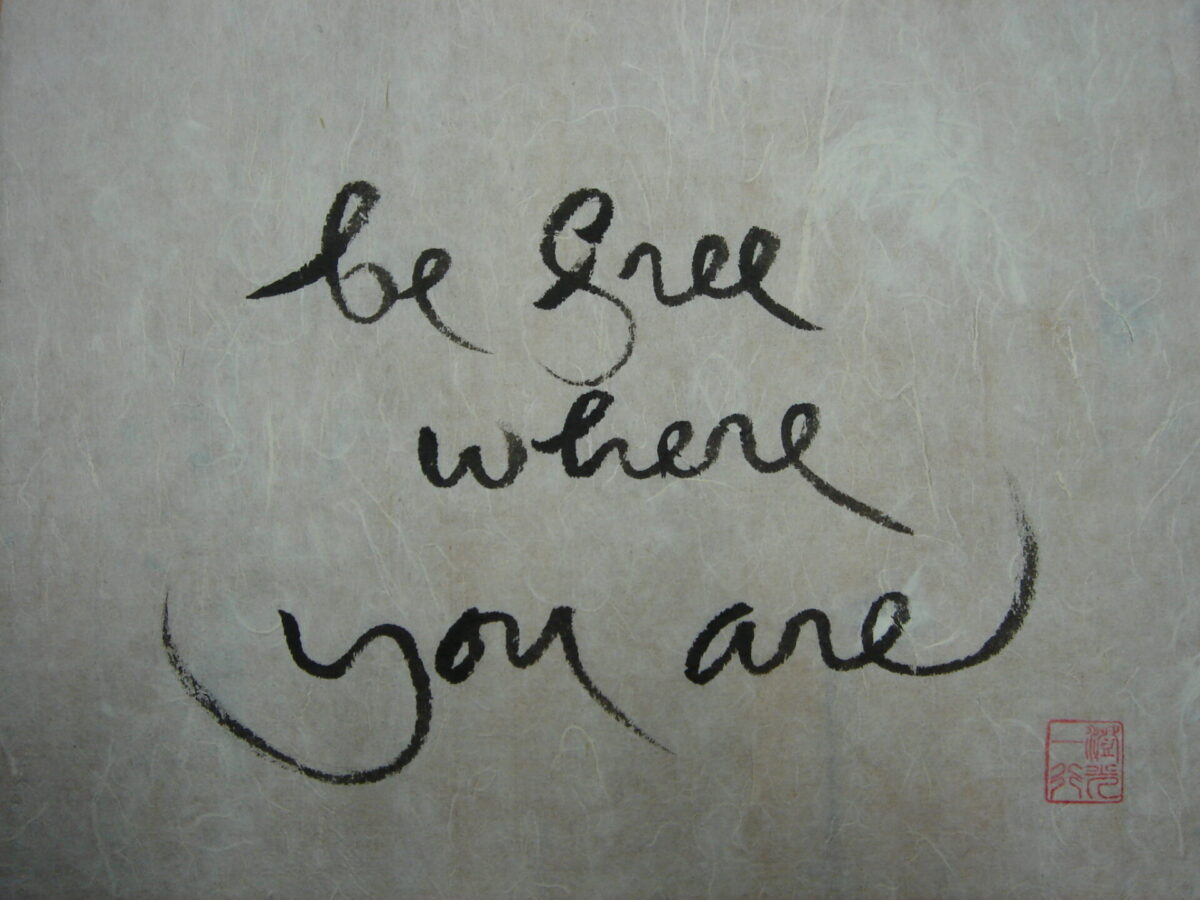

This freedom—not freedom from,

from childhood habits,

from childhood fears;

not freedom to,

to open to the love enfolding me,

to know and live my truth.

This freedom—freedom with,

with habits, with fears,

with heart protected,

truth hidden deep inside.

This freedom—freedom with this moment,

just as it is. *

_________________

In the twenty-three years since, life has offered me significant opportunities to practice with my insight of “freedom with.” My childhood fears, related to the unknown and the unfamiliar, went untended. Had my loving parents been emotionally expressive, I might have entrusted these fears to them. As it was, I was alone, ruminating on my fears and planning in order to reduce my chances of negative experiences in the future. Rumination and excessive planning became part of who I was, covering up my fear.

At the time I received Lamp Transmission from Thầy, I’d been living in the Washington, DC area for thirty-five years. I’d been teaching high school math for thirty-one, married for fifteen, and enjoying being a dad for fourteen. My life was familiar to me. I was mostly occupied with doing. Conditions seldom watered my negative seeds. Attending Sangha and being on retreats provided all the peaceful respite for being I seemed to need.

Six years later, in 2007, I retired from high school teaching. The following year my partner Elisabeth and I moved to Putney, a small town in rural Vermont, US. I left behind my identity as a schoolteacher, my daily schedule of classes, my Sangha, my friends, my home—all that had been familiar to me. Arriving in Putney, I hoped to offer mindfulness to local schools, but that failed to materialize. I was adrift. It was time, I realized, to call on “freedom with.” With that insight I adopted an attitude of curiosity. I began to write weekly “Vermont Reflections,” which I sent to friends and family members. This practice helped me focus on what was present in my life, rather than on what I had left behind. However, I still had plenty of empty hours to worry about what the future might hold. My worries were realized early in our second year in Vermont when I came down with an undiagnosed illness that laid me low. No Western or Eastern treatment helped. Weak and spending much of my time in bed, I read and listened to music. I rested, letting myself just be. This was a freedom I hadn’t experienced before, truly freedom with.

A year later, an acupuncturist introduced me to Chinese qigong practice, where I learned to give and receive qi energy and to circulate it through my body. I began what would become a twice-daily practice, accompanied by a recording of Plum Village monastics chanting to Avalokiteshvara, the bodhisattva of compassion. In their chant they sent compassion to themselves, to a loved one, and then out to the world. I silently joined them. All the while, my heart was softening and long-held tensions in my body were beginning to release. Without my conscious awareness, I was opening to the love surrounding me, and I was developing a foundation for knowing and living my truth.

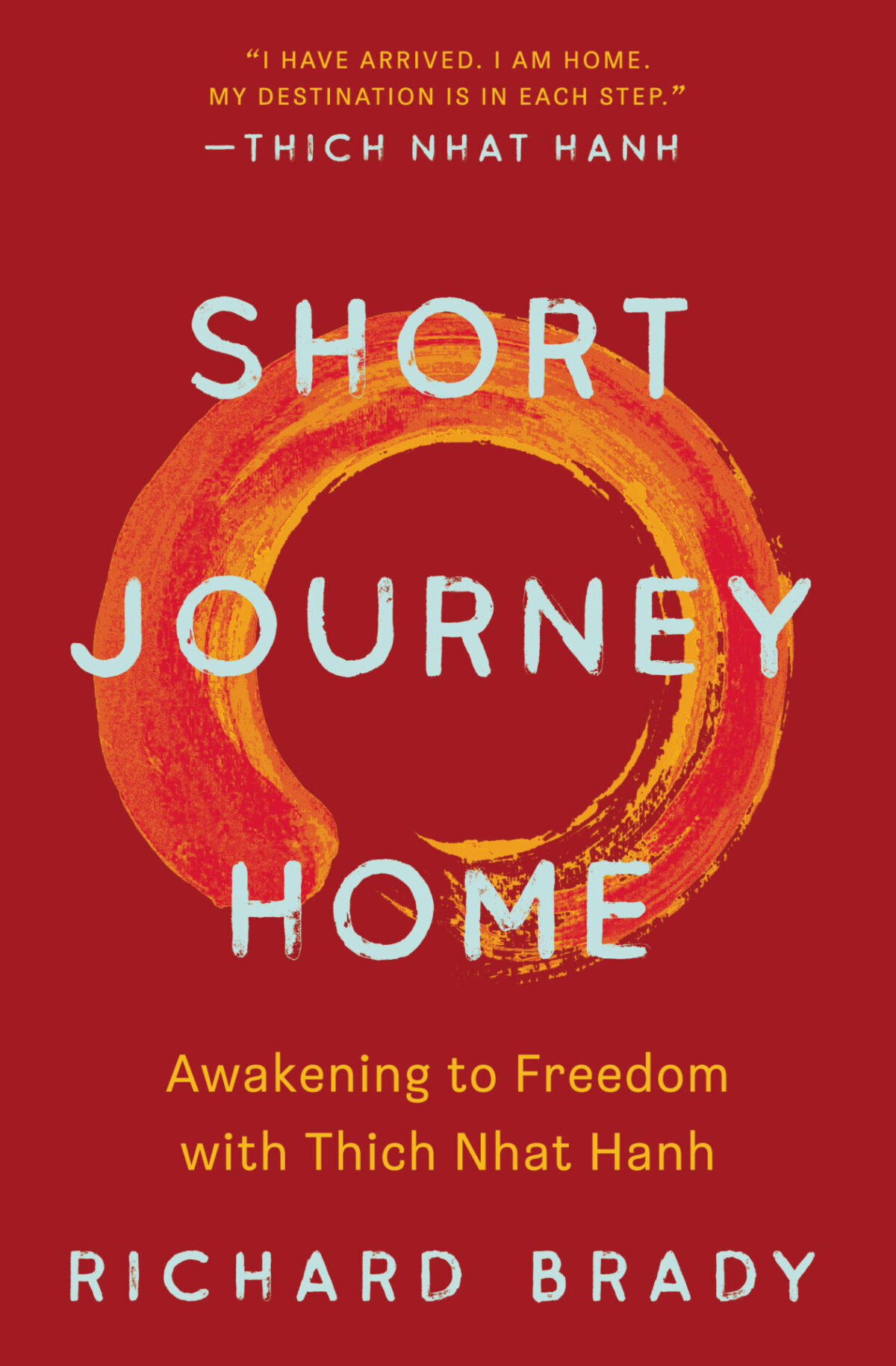

* The first portion of this article is adapted from Short Journey Home: Awakening to Freedom with Thích Nhất Hạnh by Richard Brady, Parallax Press, 2024.