Feeling safe and secure in the island of self

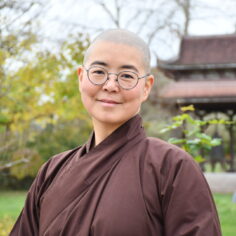

By Sister Trai Nghiêm on

Being an island unto yourself

Sometimes people ask, how can we take refuge in the Sangha and take refuge in oneself at the same time? Don’t these two practices conflict with each other? In light of nonduality and my own experience of the practice in Sangha over the past twelve years,

Feeling safe and secure in the island of self

By Sister Trai Nghiêm on

Being an island unto yourself

Sometimes people ask, how can we take refuge in the Sangha and take refuge in oneself at the same time? Don’t these two practices conflict with each other? In light of nonduality and my own experience of the practice in Sangha over the past twelve years, I know in my heart that the two ideas are not different from each other. Still, I had not yet been able to clearly explain why.

One day I saw the phrase “be an island unto yourself” written in Chinese (自洲自依). When I first heard the word ‘island’ in this context, I imagined a beautiful tropical island in the middle of the Pacific Ocean with coconut trees and a white sand beach—an ideal holiday destination where I am left in peace, away from the hustle and bustle of busy daily life and interpersonal challenges. In the sutra that this phrase comes from, though, a “just leave me alone” kind of island is not what the Buddha was referring to. When we study sutras, deciphering Chinese characters sometimes helps us deepen our understanding of the Buddha’s teachings.

We ARE the river, and taking refuge in an island doesn’t mean that we abandon the river in search of someplace else that is more peaceful, but that we learn to flow and to grow as a beautiful river...

In Chinese there are two different characters for island: 島 and 洲. The character used in the sutra is the second one, which denotes a sandbank in a river. But of course! The Buddha walked as far as he could to spread the Dharma but he never reached the coastal regions so he probably never had a chance to see a tropical island in the middle of the Pacific Ocean.

The Buddha traveled by foot to spread the Dharma in the northeastern region of India. There are many rivers born from the Himalayas in the region. At times, he even had to cross a river, perhaps under dangerous conditions. So when the Buddha gave the teachings on taking refuge in the island of self, I think he had in his mind the image of crossing a river with a strong current. The river is a metaphor for our five skandhas—the form (body), feelings, perceptions, mental formations, and consciousness. These five elements are flowing in us constantly, changing every moment. We ARE the river, and taking refuge in an island doesn’t mean that we abandon the river in search of someplace else that is more peaceful, but that we learn to flow and to grow as a beautiful river: a river born on top of a mountain as a tiny stream that becomes more majestic, expansive, and peaceful as we journey towards the ocean, passing many sandbanks on the way. Though at times the current may be rough and we may face life-threatening situations (in reality and also due to constructs of our minds), knowing that we have islands in ourselves that we can take refuge in to recuperate, to heal, and to take care of ourselves, we can be confident in our ability to continue the journey.

The gift of nonfear

In Buddhism, traditionally we say that there are three kinds of gifts that we can offer one another. The first one is the gift of material things (財施); this is offering what other people need. The second is the gift of the Dharma (法施). The third is the gift of nonfear (無畏施). I never really understood why we often hear that the third one, nonfear, is the most important gift that we can offer each other, even more important than the Dharma. I contemplated this traditional teaching for a long time, unable to understand how the gift of the Dharma couldn’t be the most important.

Why is nonfear so important? Let’s look at another way to say nonfear. I think we can translate it as “safety,” as feeling safe and secure. When I look at our community, I see it as a place that’s very safe, where everybody is kind to each other (for the most part, right? As long as no one is having a bad day!). When everybody’s a practitioner, a safe place tends to be created. Even so, even in places like Plum Village, from time to time I hear somebody say, “Oh, I don’t feel safe here.”

I see more and more, with the current state of our world, how important it is for each individual to learn the art of offering safety to one another.

I think if we want to be happy and to live peacefully the most important thing—the foundation for happiness—is that we feel safe being alive, that we feel safe being who we are in our body, and that we feel safe where we are living—in our room, in our hamlet, in the community, and in the surrounding society. I see more and more, with the current state of our world, how important it is for each individual to learn the art of offering safety to one another. It is when we’re feeling safe and relaxed that we can be the best version of ourselves, can be in touch with our Buddha nature, the awakened mind, and allow our insight and beautiful qualities to shine through. When we are happy, we are kinder to each other. But as soon as we are not feeling safe, as soon as we feel threatened for whatever reason—including being triggered by something that happened in our past—we are no longer relaxed. We tense up, we become prisoners of our own perceptions, and now whatever we hear or see could be interpreted as a threat or attack. We go into defensive mode, or even into aggressive mode. From there, small conflicts easily arise; without awareness, these small conflicts can get bigger and bigger until they turn into a huge block. We see this pattern in our daily interactions all the time, both at an individual and collective level.

Sometimes even something as simple as saying “How are you?” to someone, if the person’s not feeling at ease, not feeling safe, can lead to a defensive or aggressive response. “Why do you ask?” they may say, perhaps causing you to wonder what you did wrong. This simple example shows the importance of first offering ourselves the feeling of nonfear, the feeling of safety. Grounded in this feeling, we don’t need to fear others for no reason or to look at them with suspicion.

As human beings, the energy of fear is in us—it’s an important element of survival mechanism. But if we cultivate enough mindfulness, love, and compassion, we can take good care of our fear and by doing so we can generate relaxation and safety in our own body and mind. From this feeling of safety, we in turn can offer the energy of nonfear to those around us.

Widening the river

The path of practice is both individual and collective at the same time. In the beginning, we are a small stream. As we continue our journey through all kinds of turbulence, our boat can get flipped by big waves and we may get struck behind boulders. Knowing that there are always islands in the river where we can take refuge, we can continue to enjoy the journey and allow our river to expand so that we can create space for more and more.

As a practitioner, I do not want to build a wall around myself. I do not want to say, I just want to focus on my sitting meditation and I wish to stay in this peaceful, quiet space without being disturbed. As a practitioner and also as a disciple of Thầy, as a continuation of Thầy, I aspire to practice widening my river to include more and more things without discrimination: including things that are toxic, so to speak; things that are very difficult to receive.

The Buddha taught that if you put a handful of salt in a small bowl of water, it will be so salty that you cannot drink it. But if you throw the same amount of salt in a big river, you can still drink that water. It is the same for us. Thầy says, “If our heart is small, then those words, that action, that injustice will make us so angry. A small injustice will cause us many sleepless nights. If our heart is large, like the river, then those words will not have any effect on us, that behavior and that injustice will not have any meaning. We can continue to smile, we can continue to be free, peaceful, and joyful as we were before.”

A letter to Thầy

We received a letter from someone in prison that I was very touched by. It’s a letter to Thầy, but it’s also written to each one of us who practices mindfulness. I will modify it a little bit to maintain the privacy of this person, but I would like to read it to you because it is written for all of us.

24th September, 2021 Dear fellow human, Howdy. I pray you are well. I also hope this letter gets to you. This is in reference to Thích Nhất Hạnh. Last I heard, he was in the hospital. I hope he is still with us because I want him to hear this. My name is H. I am a thirty-one year-old transgender girl. I am in prison for a crime I did not commit. In the state where I live, it does not require any evidence to be convicted for the crime for which they indicted me. I get out of prison in December 2032 and I am going to be the first person to find out what they will do if you refuse to leave prison. In truth, I am happier now than I have ever been in my entire life. This is thanks to Thích Nhất Hạnh’s wise words in his book, The Heart of the Buddha’s Teaching, which I read in the county jail. In December 2017, I was arrested for this crime. The following September I discovered Buddhism. By December 2018, I chose to become a Buddhist and by April 2019, I decided I want to be a bodhisattva, thanks to Thích Nhất Hạnh. I am studying all the schools of Buddhism and every other religion in order to help humans attain enlightenment in their own language. Prison is the perfect place to help people. I have forgiven everyone from my past for their unjust actions. I have love for all sentient beings. People here think it’s weird that I won’t even kill the ants that bite me. Someone recently had some soup and a bunch of cookies that the ants got into and they threw them out. I got them all and the ants walked away from the cookies when I opened them and just left the soup alone after I got it. It was amazing, and I didn’t kill a single one of them. Anyhow, I can’t thank Thích Nhất Hạnh enough. I’m so happy and satisfied, and my suffering is very minimal. I love you, Thích Nhất Hạnh, and I love all of you in Plum Village. I am freer now, in prison, than I’ve ever been. Thank you all.

When I read this letter, it really inspired me to practice better. We have such wonderful conditions here in the practice centers, but for those of us living here permanently it’s very easy to take these favorable conditions for granted. When I read letters from our friends who practice in prison, I feel very inspired. I have also visited prisons in the US and practiced with the inmates. Many of them practice really diligently and very well, very deeply. Just knowing that there are friends on the path practicing everywhere in the world gives me a lot of energy. So, I want to thank this friend in prison. She will not hear this talk, but I hope that she can receive the energy of our practice where she is.

The more I practice, the more I’m convinced that nonfear is the best kind of peace work, the best kind of gift we can offer one another no matter what our background is. With our own energy of practice, we can create a safe space where we can all be our most relaxed, our most peaceful, and also our most open and receiving self. We can be in harmony with others only when we are feeling at home in our own island, in the island within.

This is based on an excerpt from Sister Trai Nghiem’s Dharma talk from the Rains Retreat, “Balancing the Inner Artist, Warrior, and Meditator” on October 28, 2021, at the Assembly of Stars Meditation Hall in Lower Hamlet, Plum Village, France. You can listen to the full Dharma talk and the orchestral rendition of The Island Within on the Plum Village YouTube channel. Transcribed by Elaine Fisher. Edited by Hisae Matsuda and Miranda Perrone.