By Therese Fitzgerald

While at Plum Village this summer, Boris and Gallina, our Dharma friends and Reiki healers from Moscow, suggested that Arnie Kotler and I stop in Riga, Latvia, on our way to Russia to lead a mindfulness retreat for the community there. “Mindfulness practice is essential for real Reiki work, and Reiki is a natural expression of mindfulness,” Boris said, and he began communications with Juri Kutirev, the founder of “Jonathan,” a Latvian organization to promote self-awareness and understanding.

By Therese Fitzgerald

While at Plum Village this summer, Boris and Gallina, our Dharma friends and Reiki healers from Moscow, suggested that Arnie Kotler and I stop in Riga, Latvia, on our way to Russia to lead a mindfulness retreat for the community there. "Mindfulness practice is essential for real Reiki work, and Reiki is a natural expression of mindfulness," Boris said, and he began communications with Juri Kutirev, the founder of "Jonathan," a Latvian organization to promote self-awareness and understanding.

A few days before we arrived, the last Russian troops pulled out of Latvia, ending 50 years of occupation. Since the 13th century, Latvia has been occupied by German, Swedish, and SovietyRussian forces, except for a brief period between 1917 and 1940. Latvia is entering a time of strong nationalism, which, we would learn, has its positive and negative aspects. Juri told us that he and other Russian-Latvians have no citizenship because their families did not live in Latvia before 1940, even though he and his children have lived only in this country.

The afternoon we arrived, we were interviewed for that evening's TV news by a woman who had read two of Thay's books. While her camera crew was waiting to get on with the interview, the woman asked us about the nature of our visit and the benefits of mindfulness practice. "People here want to blame someone else for their troubles. How can meditation help them?" During the taped interview, we discussed the process of calming and looking deeply, establishing sovereignty over oneself, and caring for one's states of mind through meditation.

Eighty people attended the three-day retreat held in Jurmala on the Baltic Sea. Five children formed a wonderful Sangha of practice with round pebbles gathered from the forest. (They searched in vain for pieces of amber amidst the seaweed!) Walking meditation through the pine forest to the calm blue sea was particularly enjoyable, and the whole retreat was full of delight thanks to the happy Sangha of Jonathan staffpeople, who took care of every detail with thoroughness and kindness. Tea meditation especially revealed many beauties of Russian, Latvian, Belorussian, and Ukranian cultures in the form of songs, poems, proverbs, and jokes. ("In every joke, there is a little joke," Juri told us.)

The retreatants asked very practical questions, such as, "Do you ask your teacher questions?" and "How does practice make you calmer?" On our last day in Riga, we met with a journalist whose incisive comments inspired us. Imagine our delight when she took out her glasses' case filled with five beautiful round pebbles gathered at Jurmala to practice conscious breathing during difficult phone calls!

Amie and I went next to St. Petersburg to help our friends there in last-minute preparations for a visit by Thay, Sister Chan Khong, and Sister Jina the next day. After a 14-hour train ride from Riga, we were swept off to review the schedule for the retreat and to make sure accommodations were in order. It turned out that a crucial fax had never made it into the hands of the organizers, and so there was some rearranging to do at the last minute. After a very full day traveling around the city settling these affairs, we sat with the St. Petersburg Sangha under the golden linden and oak trees at the international airport, enjoying bread, cheese, and juice, discussing Igor's interest in becoming a monk, and waiting in peaceful camaraderie for Thay's plane to arrive.

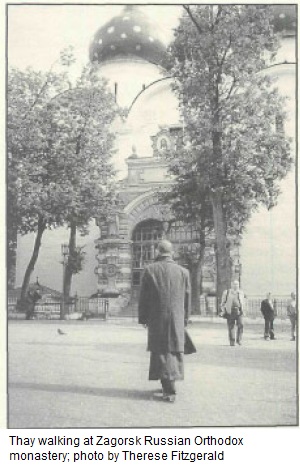

The next morning, Edward and Igor took the five of us for a walk in the Summer Gardens. As we were leaving, Thay paused alongside a canal facing the spectacular Church of the Resurrection and recounted a passage from the Vietnamese classic poem, The Tale of Kieu, about two lovers. "The woman went back to the home of her lover and saw him asleep at his desk. The young man looked up and said, 'Is this a dream or are you really there?' The woman said to her beloved, 'Look as if it is the first or the last time you see my face.'" We contemplated anew the beauty before us and the wondrousness of our being together in St. Petersburg.

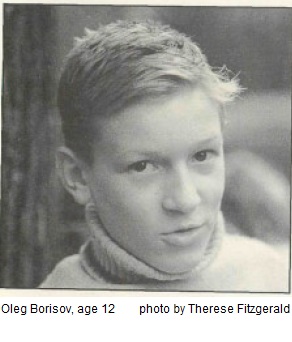

Walking up the stairs of the Buddhist Temple—established in 1897 with the support of Czar Nicholas II but shut down for 60 years under Stalin and his successors—Thay commented softly, "I am aware of all the previous suffering." Thay's lecture was attended by 250 people, and half that number attended two Days of Mindfulness, which had been publicized only by word of mouth. The Buryatian monks and novices at the temple were attentive, respectful hosts. Thay's Dharma talks on conscious breathing to establish calm were nurturing for the many who attended. The walking meditation path wound through trees between two canals sparkling in the autumnal light. The 20 Reiki healers among the participants were especially spirited and offered songs at the stopping place by the canal, complete with guitar and birch-bark kazoo. Forty people received the Five Precepts the last day of the retreat. Twelve-year-old Oleg Borisov, one of our steadiest co-practitioners during our stay in St. Petersburg, wrote this description of his continuation of the practice:

"This was my second experience of a Day of Mindfulness, and I felt some progress in my meditation. Now both walking and sitting meditation were easy for me. The day began with the explanation of some phrases which aid in concentrating the breath, such as "I am solid, I am free." I liked this, and I wanted to meditate not for just a few moments, but much longer. The day was sunny for walking meditation in a park, and, thanks to that, I entered deeply into the meditation. The whole world was transformed before my eyes. Everything around me was new, fresh, wonderful. It was amazing! I smiled.

"During lunch, it was hard for me to concentrate on the food at first because I was so hungry. It was easiest to concentrate on the bread. When tea meditation began, I was asked to partake in the opening ritual by carrying a cup full of tea in a meditative way to the tea master. After that I sat in place and began to drink my tea. The tea and cookies were much more delicious than usual. Then I entered into a state of deep meditation while everyone sang.

"During the second day we practiced much more. In the beginning we did exercises for half an hour, then sitting and walking meditation inside. That worked well for me, and I felt at home. After Thay's Dharma talk, we went outside to do walking meditation, and it was much harder for me to concentrate. Something was getting in my way, even though, in comparison to the previous day, there were not so many distractions (insects, for example, that we had to brush off the road onto the earth). At lunch, I began to recite the gathas. When I opened my eyes, I saw food on the plate before me. Then I recited a few more gathas in gratitude to the person who gave it to me.

"Total relaxation was very easy for me, and soon I found myself in a blissful state where nothing could shake me. I was fully aware of my body and completely relaxed. When we got up, I didn't quite feel right. There was some kind of residue. Later when I practiced relaxation it repeated but not as strongly. During this time I decided to take the Five Precepts. During the ceremony I suddenly felt waves as if there were some kind of energy moving inside me. In general there were more feelings coming up on this day than on the previous day.

"These days were fruitful. Along with the Dharma name "Mindfulness of the Heart!' I also received encouragement to practice all day long. When I see water flowing from the faucet, I remember I am only here and only now, and I smile."

Thay, Sister Chan Khong, Sister Jina, Arnie, and I lived in great harmony as a "family" with our St. Petersburg hosts, the Borisovs. Four of us stretched out our bedding on the living room floor every night, and we prepared our meals together and ate in deep appreciation of the goodness of Russian bread, potatoes, tea, and also the wonderful Vietnamese cooking of Sister Chan Khong.

On the last night of our stay, we met with members of a potential core Sangha of mindfulness practice, while another meeting was going on in the kitchen between Sr. Chan Khong and Orris Publishers about publishing a volume of four of Thay's books this January—Present Moment Wonderful Moment, Touching Peace, The Diamond That Cuts Through Illusion, and The Moon Bamboo. Thay spoke about the need to listen carefully to others and not to be too attached to our own ideas. "Don't think, 'My idea is the only one worth considering.' We need to gather as a Sangha and make decisions together after listening to several viewpoints." Then Sr. Chan Khong offered the Sangha 100 of Thay's books from Orris to sell in order to help the Sangha cover such expenses as rental of a place for practice and inviting teachers to come. Thay entrusted the bell of mindfulness to Julia with instruction, and a set of books in English was entrusted to Edward for the use of the whole Sangha.

When Sasha requested that we also visit other meditation groups throughout the former U.S.S.R., Amie suggested, "Just as Thay says that the best way to take care of the future is to take care of the present moment, I think the best way to take care of other Sanghas is for us to take good care of the Sangha here." After several previous visits, we could see that it is not easy for mindfulness practice to take root. Our friends in St. Petersburg are very much in our hearts and minds, and we wish them success in their efforts to practice together.

In Moscow, we were greeted by unseasonably warm weather and Sangha members offering dozens of fragrant roses. That evening, Boris told us the story of his pacifist resistance to the communist authorities. Finally, he said, "Our first daughters were born during the time of Brezhnev, and you can see the psychological scars they bear from the tension and oppression of those times Masha was born during perestroika, and you can see in her some lightness. But Katya, born after the fall of communism, is a completely different personality, so open and free."

The next morning we did walking meditation among the cathedrals of the Kremlin. In the evening, Thay gave a public lecture to the local Vietnamese community, so beleaguered with violence, fear, and insecurity. Thay spoke for nearly three hours about the practice of conscious breathing, the need for something beautiful and true to believe in, how wrong perceptions are the source of much of our suffering, and the need for clear communication with loved ones to nurture our love and understanding. In response to the question, "If the Buddha was a man, why do we offer incense and prostrate to him?", Thay spoke about honoring the Buddha within. When someone commented, "In the face of so much violence and hatred here towards the Vietnamese, I feel overwhelmed and hopeless," Thay gave practical suggestions about maintaining calm as we work to overcome oppression and injustice.

On Thursday, Thay gave a lecture to 300 people, and on Friday, we headed to the retreat site, where Thay concentrated again on the problem of holding too strongly to ideas rather than practicing mindfulness of the present moment. "One ideology imposed on people can cause a lot of damage. We have to be very careful where we put our faith." He articulated the Five Powers—faith, diligence, mindfulness, concentration, and understanding—as a way of proceeding from a failed ideology to a life of authentic contact with reality.

One question, "Is Thay going to speak about the Dharma or just his experience?" prompted an description of the difference between the written or spoken Dharma and the "living Dharma." Thay responded to the question, "Are you enlightened?" by saying, "When you ask such a question, you need to ask, 'enlightened about what?' Enlightenment is always enlightenment of something." Thay emphasized with the Muscovites how we can be enlightened many times in the course of a day if we live mindfully. This seemed like the right medicine for people who tend to mystify spiritual practice. Forty more people received the Five Precepts in a ceremony in Russian and Vietnamese. Thay seemed energized and happy at the end of the retreat as he served me a cup of sweet beans and ginger he had cooked himself, and we enjoyed them and the majestic birch forest outside the window.

Several core Sangha members stayed at the retreat site, and on Monday morning we practiced walking meditation with Thay and had a Dharma discussion about practice, communication, and Sangha organization. Several Russian friends gathered mushrooms in the forest, which they gave to a delighted Sister Chan Khong.

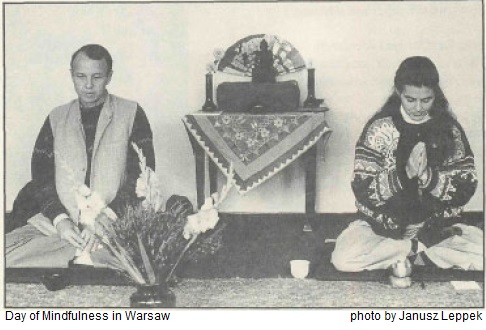

Thay and the Sisters went home to Plum Village, and Amie and I went on to Warsaw. Our first evening there, we attended a Jewish holiday ceremony (Simchat Torah) at the only synagogue in the city. It was encouraging to feel the revitalization of a faith and practice that had suffered near-annihilation. Men, women, and children danced in circles, celebrating the Torah in Hebrew song. The next day, with the help of Jewish-Buddhist friends from Warsaw, we ventured forth to Lodz, the home of Arnie's maternal ancestors. We sat briefly inside the Jewish community center's temple and witnessed a heated discussion about the Torah among several elderly men standing around the sacred text. Then we went upstairs to a dark room off the heavily scented kitchen to meet with Mr. Praszkier, the head of the temple, who agreed to look through his records for the death certificates of Arnie's great-grandparents. He wrote some names and numbers on a piece of paper and telephoned the cemetery gatekeeper, who guided us along a wide path carpeted with yellow leaves, while the autumn sunlight filtered through the changing maples. We walked past grand tombstones of Jewish magnates to a wild maze of poorer tombstones contending with undergrowth. "Come and see the grave of my grandmother's mother," Arnie said as he took my hand and walked me to a gravesite not quite five feet long covered with green moss, the headstone beautifully carved in Hebrew. We touched the moss and breathed in contemplation. It was sobering to walk among the untended graves of so many others who no longer have living relatives.

The next evening we joined students of Kwong Roshi for sitting meditation, chanting, and tea in their zendo in Warsaw's Old Town. Everything was familiar from our experience in Japanese Soto Zen, except there was a painting of the Black Madonna on the altar and the chants were in Polish as well as in Japanese. When one of the students asked how the chanting sounded to me, I said that I did not know why, but it sounded to me very much like Latin. He said that Latin is part of the Polish linguistic heritage, that from the 14th to the 18th centuries, Latin was spoken by the Poland's aristocracy. In a discussion over tea, Arnie and I expressed our appreciation for the calm refuge of their zendo and the applicability of Zen practice and insights to family, community, work, and political life.

One hundred people attended Amie's public lecture, and 30 joined us for a Day of Mindfulness the next day in a cozy garden house in an orchard-filled yard. Arnie spoke about joy and peacefulness as gauges for one's meditation practice. He related many stories about the effects of Suzuki-roshi and Thich Nhat Hanh's simple, deep, quiet, and joyous presences. There was time to hear from each participant—their needs, anticipations, and actual experience of the practices. We ended with a meeting about mindfulness practice as an adjunct to the already established Zen practices in Warsaw. Those who have taken responsibility for holding Days of Mindfulness since Thay's visit in 1992 felt the need to share the responsibilities. It was a relief to acknowledge how important thing it is to practice mindfulness while taking care of the details of organizing the practice!

We had time before leaving Europe to marvel at Warsaw's Old Town. A film on the death of so many thousands of soldiers and civilians and the destruction of Warsaw by the retreating Nazis opened my heart to the tenacious spirit of Warsovians and made the walk through the cobblestone streets amid reconstructed buildings decorated with paintings, woodwork, and mosaics precious and real. Exchanges with individual Sangha members were a delight and moved us. Marisha remembered when there were only the foundation stones of the majestic palace of the square. Tanna remembered being so hungry as a child after the war that she ate plaster for its calcium. Walks together, visits to churches listening to services in Polish, meals at homes and favorite restaurants, and sharing tea gave Warsaw a very special meaning.

We felt very warmly welcomed back to the U.S. when we arrived in New York City in time to enjoy a spectacular sunset. The silhouette of the Verrazano Bridge laced with light against the golden-red sky ahead and stunning views of the Manhattan skyline and the bay on either side brought home to us the feeling of bountiful beauty. At the mindfulness retreat for veterans and others at Omega Institute, we were greeted by many loving faces of Order of Interbeing members as well as many open faces of newcomers to the practice. Sitting under a glorious maple tree observing people as they began to settle into natural walking meditation, I felt blessed to be with friends maturing in the practice of mindfulness as individuals and as a caring Sangha.

Therese Fitzgerald, True Light, is the director of the Community of Mindful Living.