By Maureen Chen

Three years ago I took an introductory class at New York City’s calligraphy guild, the Society of Scribes, where I learned to write the alphabet with a pen that has to be dipped into a bottle of ink. Because of the precise and skillful hand movements needed to use this pen, calligraphy is an excellent practice for developing mindfulness.

By Maureen Chen

Three years ago I took an introductory class at New York City’s calligraphy guild, the Society of Scribes, where I learned to write the alphabet with a pen that has to be dipped into a bottle of ink. Because of the precise and skillful hand movements needed to use this pen, calligraphy is an excellent practice for developing mindfulness. Dipping the pen into ink after every few words is akin to repeatedly stopping for a mindfulness bell.

The word “calligraphy” consists of the Greek words kalli, meaning “beautiful,” and graphein, meaning “to write.” Calligraphy is writing that has been practiced to a high degree of skillfulness and created with great mindfulness, so that the result is a beautiful work of art. In contrast, one’s everyday handwriting is written quickly, out of habit, and is not meant to be art. Much painstaking practice was needed before my writing even began to look beautiful.

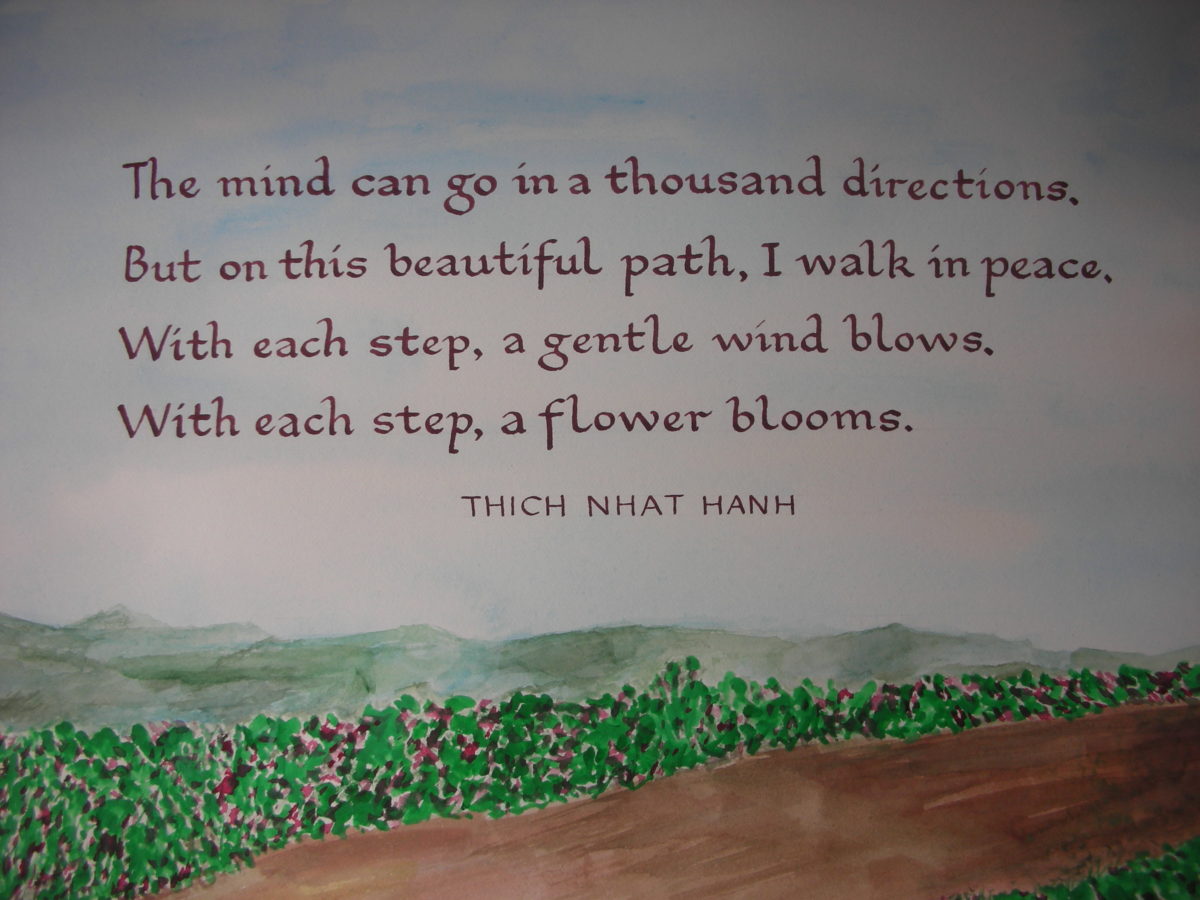

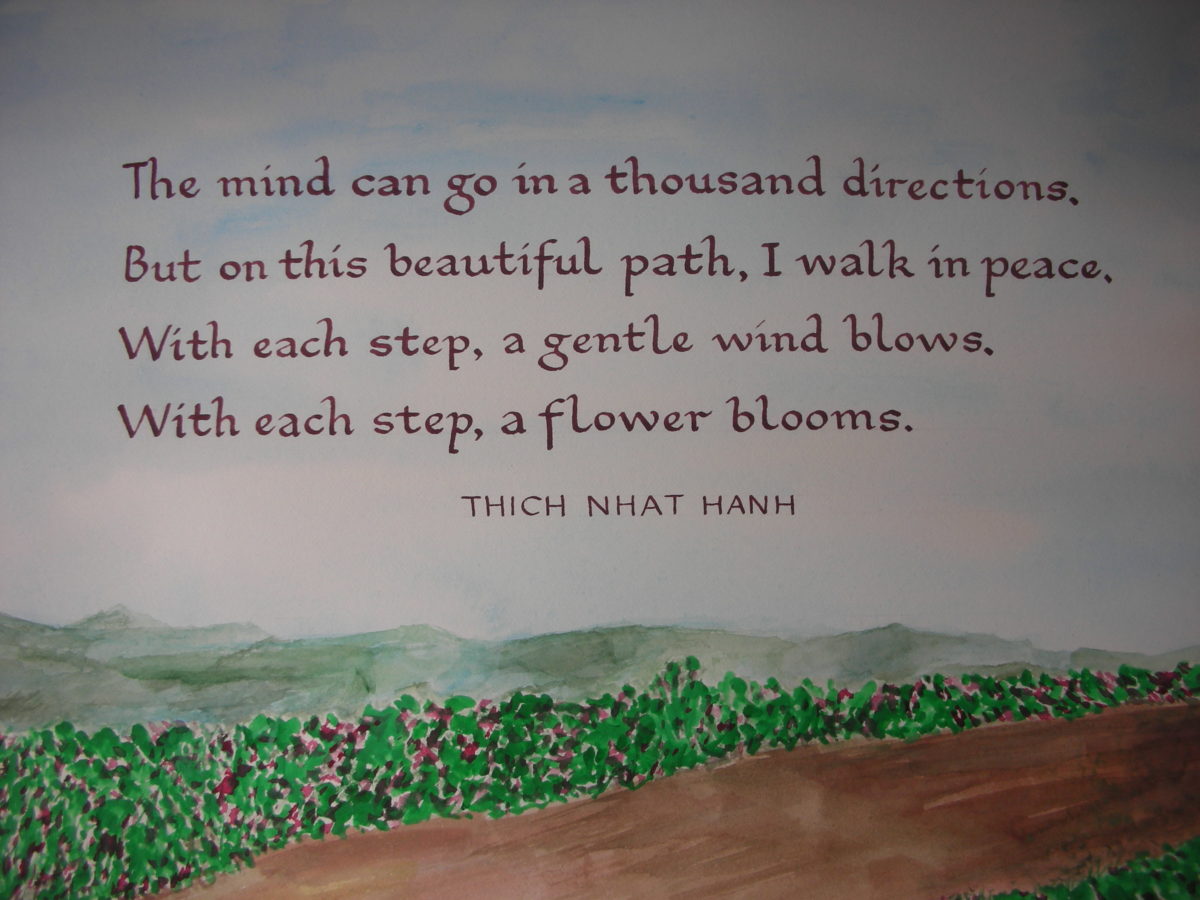

I became a member of the Society of Scribes, one of many calligraphy guilds worldwide, which has classes and events where I could improve my skills and meet other calligraphers. Volunteering at the annual year-end members’ exhibition motivates me to create work to exhibit. For the 2011 and 2012 exhibitions, I copied in calligraphy two of Thay’s gathas and the saying: “Don’t just do something, SIT THERE.” As I searched for texts that would have a calming effect on viewers, I inadvertently discovered that calligraphy can be a Dharma door.

Between exhibitions, I used calligraphy to make greeting cards and address envelopes. I made Thanksgiving cards for a local nonprofi to distribute to homebound seniors with their holiday dinners and addressed invitations for another nonprofit’s fundraising event. Thus, I found that calligraphy could be a means for doing social service.

Throughout the history of Buddhism, monastics and laypersons in various traditions have copied sutras as a mindfulness practice. A recent exhibition of sutras, mainly the Heart Sutra, copied in calligraphy and illustrated by contemporary Korean monastics and laypersons, inspires me to try this when my concentration is deeper.

Ultimately, the styles, techniques, and materials of calligraphy, which vary depending on time and place, matter far less than one’s mindfulness while practicing. In this digital age, while typing on keyboards and screens allows us to write at technology’s speed, practicing calligraphy provides the slowness needed to experience the miracle of mindfulness. Typing can be compared to putting the dishes in the dishwasher to get clean dishes. Calligraphy is like washing the dishes to wash the dishes.

Maureen Chen is a co-facilitator at Morning Star Sangha in Queens, New York. As a consequence of pursuing calligraphy, she learned of Thay through Seattle calligrapher Gina Jonas, who quoted from The Miracle of Mindfulness in her article, “Calligraphy as a Spiritual Way.” The occasion of Thay’s calligraphy exhibition in New York City from September 7 to December 31 inspired Maureen to write this article.