By Sister Peace in June 2011

I sat here at this same lotus pond in New Hamlet just a few short years ago and wrote my letter of aspiration to become a nun. And here I sit again, this time writing a letter to Thay and my friends, a letter that shares what I will call an “ancestral insight.” During my time as a monastic here in Plum Village,

By Sister Peace in June 2011

I sat here at this same lotus pond in New Hamlet just a few short years ago and wrote my letter of aspiration to become a nun. And here I sit again, this time writing a letter to Thay and my friends, a letter that shares what I will call an “ancestral insight.” During my time as a monastic here in Plum Village, many of my most treasured moments have been the realizations of these deep insights.

In monastic life, form and conformity are an important part of our practice. One of the expressions of form is the mode of dress we assume. Luckily, we wear simple robes, and on occasion the nuns wear head scarves. I’ve always admired my dear sisters when I’ve seen them with the head scarves and robes as they are literally dressed head to toe in brown—the color of the earth and a reminder of our link to those who work the land and live a simple life. Their beautiful round faces glow with joyful smiles beneath heads wrapped in the earthen color.

Yet, when I looked in the mirror and saw myself with the same scarf, I didn’t see—I couldn’t see—the same beauty. In fact, what I saw was not beautiful at all. It was disconcerting, to say the least; I felt I looked funny and out of place. Of course, I continued to wear my scarf despite this view, and thought, “Well, maybe I just have to get used to the way it looks.” But after more than a year, my view didn’t change, and I couldn’t get used to the way I looked in the head scarf. I began to look deeply and ask, “Why do my sisters look so nice, but I don’t?” I tried tying it on in various ways in hopes of improving the look of it, but this didn’t seem to help either.

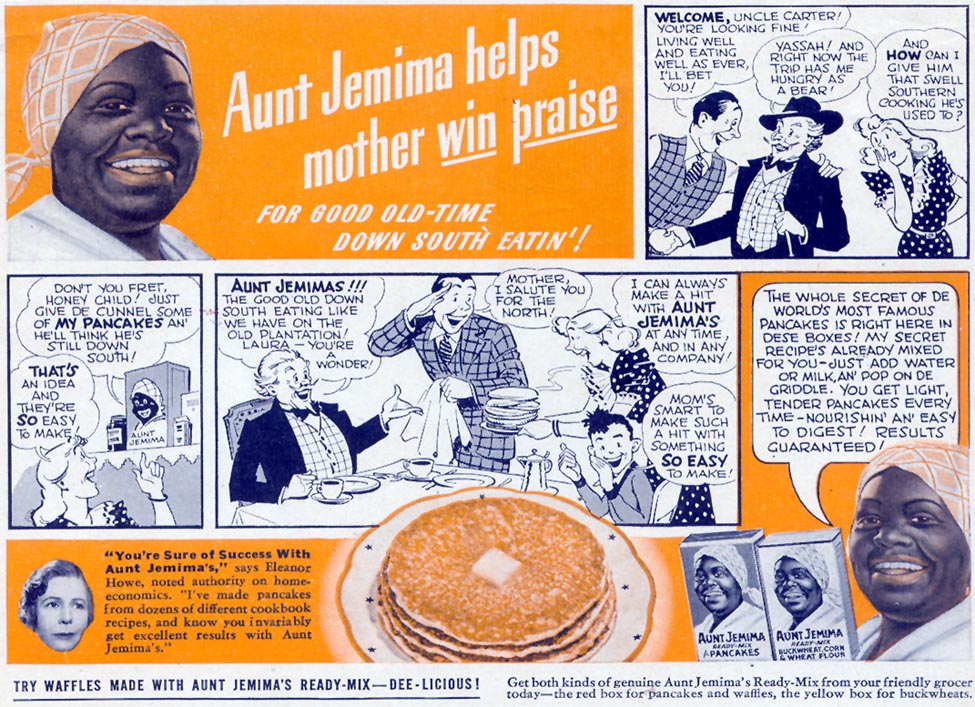

So I continued to ask this question, sitting and walking with it. And one day, when I looked in the mirror, a stunning answer came. I didn’t see myself; I saw Aunt Jemima! Aunt Jemima, just like on the maple syrup bottles and the pancake boxes of yore—that infamous trademark depicting a stereotypical African-American woman with her head wrapped in that bandana, smiling, with wide bright eyes. And the memories came flooding back, memories of days from my youth and growing up in the south, in Washington, DC. We were taught to have disdain for this cultural icon, and if we dared to wear a scarf like this as young girls, we were ridiculed and called “Aunt Jemima” in the most condescending way.*

We didn’t want to have anything to do with Aunt Jemima, least of all look like her! When I was a very young girl in the late ’60s and ’70s, there were clearly defined (though unspoken) ideas of what a young African-American girl should look like, and it definitely was not Aunt Jemima. We were somehow taught in silent ways that this important link to our history of slavery, racism, and discrimination in America was to be shunned. The mockery that was perceived when we were labeled or looked upon as icons such as Aunt Jemima, Uncle Tom, Stepin Fetchit, Uncle Ben of Uncle Ben’s rice, Rastus of Cream of Wheat, and others, only brought upon us shame and confusion.

As a young girl, I could only see the shame and “ugliness” of these icons. It is only with hindsight, the insight of mindfulness, and the daily practice that I was able to see the confusion, pain, and false sense of security which manifested as a result of this particular view. I realized in an instant, with that image of Aunt Jemima reflected back at me in the mirror, that we held what I know now to be a wrong view. Any view that causes us to see ourselves as separate is a wrong view. I realized that as a child, I had shame and fear about something I didn’t quite understand. Isn’t it interesting how our cultural icons affect us, without us ever really knowing it?

And in this wonderful instant of insight I embraced my Aunt Jemima: the Aunt Jemima in me and that is me. I exhaled, felt deep release, calm, stillness … and beauty. How could I have seen her as anything other than myself? Shunning Aunt Jemima was like shunning myself—no wonder I felt disconcerted and disconnected.

Today, I don’t deny the cavernous pain and suffering that these images and what they represent evoke in all of us, but I have learned the value of embracing them and the pain and suffering that lies in my very own DNA. I am embracing, accepting, and gradually transforming these for myself, my parents, my great-great-great-great-great grandma Mary who was a “house” slave, and my grandmother, Grammy Nanny, who worked as a domestic in an antebellum mansion in Millwood, Virginia, until very near her death at eighty-nine years of age just over twenty years ago. She cooked, cleaned, managed the household and raised two boys, who wept like babies at the funeral of their beloved Nana. For all of us and all of you, I share and embrace these memories and insights toward transformation and healing.

Thank you Aunt Jemima, Stepin Fetchit, and all the others. Thank you all for being there. Your stereotypes represent countless real people who, through perseverance, courage, and the sheer will to survive and live, did what was necessary so we—all of us, your descendants—could be free and here today. And with the art of mindful living, we can learn to embrace all parts of our ancestral history and ourselves, because in reality we are not separate but one, and part of the same continuum.

When I look in the mirror now, I sometimes still see my old friend Aunt Jemima. But with this powerful new insight, I know not to fear, not to hate, not to have shame. Instead I have awareness, smile, and say: “Hello Aunt Jemima! I know that because you are there, you are one of the conditions that made it favorable for me to be here today … wrapped in a beautiful brown robe, with a headscarf that frames a beautiful round brown face, glowing and smiling happily.”