By Mitchell Ratner in June 2002

Meeting Thich Nhat Hanh

In November, 1990 I heard Thich Nhat Hanh address a conference in Washington, D.C. The next day, with 300 others, I sat with him at the Lincoln Memorial and listened to him read poems from the Vietnam War years and reflect on his efforts to share with Americans the suffering caused in both countries by the war. Then we walked silently,

By Mitchell Ratner in June 2002

Meeting Thich Nhat Hanh

In November, 1990 I heard Thich Nhat Hanh address a conference in Washington, D.C. The next day, with 300 others, I sat with him at the Lincoln Memorial and listened to him read poems from the Vietnam War years and reflect on his efforts to share with Americans the suffering caused in both countries by the war. Then we walked silently, reverently, past the Vietnam Veterans' Memorial. I was deeply impressed by the quality of his presence, the flowing calmness of his words and actions and the remarkable effect this had on others. Sitting on a cushion at the conference, on a simple raised dais, Thich Nhat Hanh spoke softly about love, anger, compassion, about finding peace and joy in each step, in each action. His words and presence created an atmosphere of infectious serenity. The audience of 3,000 was wondrously quiet; even coughing was suppressed naturally for the duration of the talk.

Finding peace and joy in each moment was a lovely idea, but how could I weave that way of being into the fabric of my urban American life?

Plum Village Life

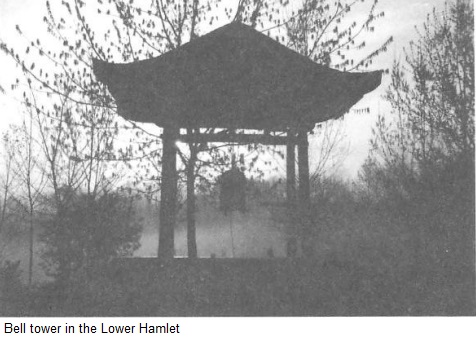

With great anticipation I set off in November 1991 for a three-month winter retreat. Plum Village was then two farm complexes or hamlets about two miles apart in the Dordogne valley, an hour's drive from Bordeaux. The region offers vistas of small farms and vineyards, gently rolling hills, historic chateaus, and picture-perfect clouds and sunsets.

Daily life at Plum Village was fairly relaxed. Before breakfast and before retiring, the community gathered in meditation halls for an hour of sitting and walking meditation and the reading of a short Sutra. Before lunch residents did outside walking meditation together for about 30 minutes, followed by the ten mindful movements, tai-chi-like stretching exercises.

Aside from the silent meals, on most days the only other scheduled activity was a work period of two to three hours. Monastics, permanent residents, and lay visitors rotated through work assignments necessary to support the community, such as making bread or tofu, working in the gardens and greenhouses cooking, and making small repairs. Twice a week, the hamlets gathered for talks by Thich Nhat Hanh.

I was very happy to be in Plum Village-there were so many wonderful things to learn. The way I had been trained to learn was through studying. I threw myself into it, reading Thich Nhat Hanh's books late into the night. I took notes, developed charts, glossaries, and Sanskrit word lists. I initiated discussions with advanced students about the meaning of key concepts, such as "emptiness" and "samsara."

Three weeks after my arrival, Sister Annabel, then the Director of Practice, asked me after the evening meditation if I wanted to gain something from my stay at Plum Village, something I could carry home with me. I thought to myself, excitedly, "Here it is, my study has paid of—Sister Annabel is going to pass on to me the central organizing principle that will make sense out of it." Her reply was not what I expected. With a slight tone of reproach she said, "Mitchell, everywhere you go should be walking meditation."

Walking meditation, as Thich Nhat Hanh teaches it, is a relaxed, slow, focused, walking with attention brought to the feet and the breath. In the meditation hall, between sittings, it is usually done with one's palms together, in front of one's chest. One walks slowly, with one step for an in-breath and one step for an out-breath. Outside the meditation hall it is usually done more quickly, with two, three, or even four steps for each in-breath or out-breath, and with one's hands held or swinging naturally at one's side.

When Sister Annabel admonished me, I already knew about walking meditation, in the sense that I understood the outer form. I had done walking meditation many, many, times, but the import of walking meditation at Plum Village had not yet entered my heart.

The Present Moment is the Teacher

What I still hadn't learned was that the essence of Plum Village was not a philosophy or concept, but rather a way of being, a practice: that we should pay attention to the present moment. The behavioral ethic of Plum Village is to mindfully carry out each activity, working calmly and giving it our full attention, whether it is cutting carrots, tying a shoe, walking to the bathroom, or writing a letter. Acting in this way, each act becomes more real, more authentic. I could see the transformative power of this practice in others. The presence I had found so remarkable in Thich Nhat Hanh when I first met him was embodied , in varying degrees, by each of the monks, nuns, and long-term residents of Plum Village.

The importance of continuous mindfulness was being constantly taught indirectly. One afternoon during a 1993 visit, I was busily sweeping a meditation hall when I glanced over to Brother Phap Ung, a young Vietnamese-Dutch novice monk, who also was sweeping the meditation hall. Something in the way he held himself, in the quality of his broom strokes, made me aware of an agitation within me, an impatience. I was sweeping to get the job done, so I could move on to something important. In contrast, he clearly was sweeping as if what he was doing was important.

Plum Village is a place of wonderment. But it is also a human community, of monastics, residents, and visitors of very different backgrounds, with different capacities and ways of embodying and expressing the spiritual lessons of Plum Village. Misunderstandings and tensions were inevitable. It was easy to get caught up in the ongoing drama of who was doing what and why. It was especially easy for me to get caught up in the drama when my feelings were being hurt, when others were not acting or responding in ways I desired. And when I was puzzled, hurt, confused, I sometimes questioned all that I had learned at Plum Village. Without really realizing it, a part of me implicitly tied the attunement to the present moment, the teachings of the Buddha, Thich Nhat Hanh as a person, and Plum Village as a community into a single conceptual package. I couldn't separate the message from the messenger.

That changed one brisk winter morning, during a stay in 1996. As usual, after his Dharma talk, Thich Nhat Hanh led the community in walking meditation to an open space in the plum orchard. Instead of returning to the dining hall for lunch, Thay took a few steps forward and repeatedly motioned for everyone to come closer. The seventy of us in the circle moved in, bit by bit, until we were closely crowded around him.

He spoke softly, in English, looking directly at us, "With each step you have to say: I have arrived. l have arrived. Whether your home is in Washington, D.C. or New Delhi, you have to come home to this moment. You have to be here with each blade of grass. This is Nirvana. This is the kingdom of God... You have to be your own hero. No one else can do it for you . You need determination. You need concentration... This is the essence, the heart. If you can take one step, you can take two. The present moment is a teacher that will always be with you, a teacher that will never fail you."

It was an extraordinary moment. Standing there in the orchard, I could feel his determination, his sincerity, his great desire to teach this simple truth, as a physical presence. And when that energy entered, it melted the bonds that had held together the conceptual package of message and messenger. Suddenly I realized that I was free to trust the present moment, wholeheartedly, unreservedly. I could trust wholeheartedly and still honor and embrace the hesitations I sometimes felt about how I or others were treated at Plum Village.

Although the realization gave me permission to have hesitations, in practice I had fewer. I found that I could be more tolerant of a perceived shortcoming because there was less riding on it. Conflicts arising out of cultural misperceptions, lack of thoughtfulness arising out of human frailties could be seen as just that, not as threats. My peace and happiness did not depend on anyone in the community being perfect, much less everyone. It came as a great relief to let go.

From Seeking to Trusting

Many of us who look for spiritual comfort do so because of the wounds we have received. We want an explanation which we think will make the unhappiness go away. One of the great gifts of Thich Nhat Hanh and of Plum Village is to turn us back on ourselves, to turn us back to our own experiences, our own lives. Thinking alone can take us only so far. The disembodied intellect can compare, contrast, and perform logical operations, but without an intimate awareness of our lived experience, we are constantly battered about, vaguely or acutely dissatisfied, hoping to solve with our heads that which can only be solved with our hearts, our heads and our awareness working together. The beginning and end points of this spiritual journey are wonderfully captured in two lines from a talk Thich Nhat Hanh gave several days before the instructions in the orchard :

"When you are alienated from your roots, you seek Buddhas. When you are in touch with who you really are, you are a Buddha."

Bringing it Home

Over the years I've looked for and found ways to bring the spirit of Plum Village home with me, to my everyday life in an American city. What helps me most are bells of mindfulness. Real bells, such as from our grandfather clock, and metaphorical bells, such as the red of a stop light, gently remind me to return to the present moment. Gradually there seems to be more calm and balance in my life, a growing inner stillness. Every once in a while, when I catch myself naturally falling into a more mindful way of doing something, such as being aware of my feet and breath as I climb stairs, I smile inwardly to Thich Nhat Hanh. I recognize that his spirit has entered my stair-walking, and that, as he teaches, the boundaries between us are more illusionary than we believe them to be and the interconnections much more real.