Losing my Brother in a New York State of Mind

By Nate Metzker

My girlfriend, Cameron, and I moved to New York City in 2005 with great expectations for her career as an educator and my career as a musician and novelist. My girlfriend’s career soon exceeded expectations. I, on the other hand, did not fare as well.

Losing my Brother in a New York State of Mind

By Nate Metzker

My girlfriend, Cameron, and I moved to New York City in 2005 with great expectations for her career as an educator and my career as a musician and novelist. My girlfriend’s career soon exceeded expectations. I, on the other hand, did not fare as well. By the end of six months, I’d run out of savings and found it difficult to locate a job that gave me time for my art.

Optimism carried me for a while, but eventually, my optimism began to wear off: gigs were hard to come by, selling music was next to impossible, and depression set in. I was attending Sangha meetings in the city, which I enjoyed, but I was not able to let go of my attachments to my version of success.

I had been at Deer Park Monastery the day it opened, and had spent a lot of time there—sometimes months without leaving—and now I returned to the monastery, thinking I could get my head together. And I did. And it was wonderful. But when I returned to the city, I began a slow descent back into depression. I started to think I needed to get back to the monastery again, but then realized: No, Nate, you need to deepen your practice where you live. I vowed that I would go back to Deer Park only when I had been able to become peaceful and happy in New York City.

Transforming New York City

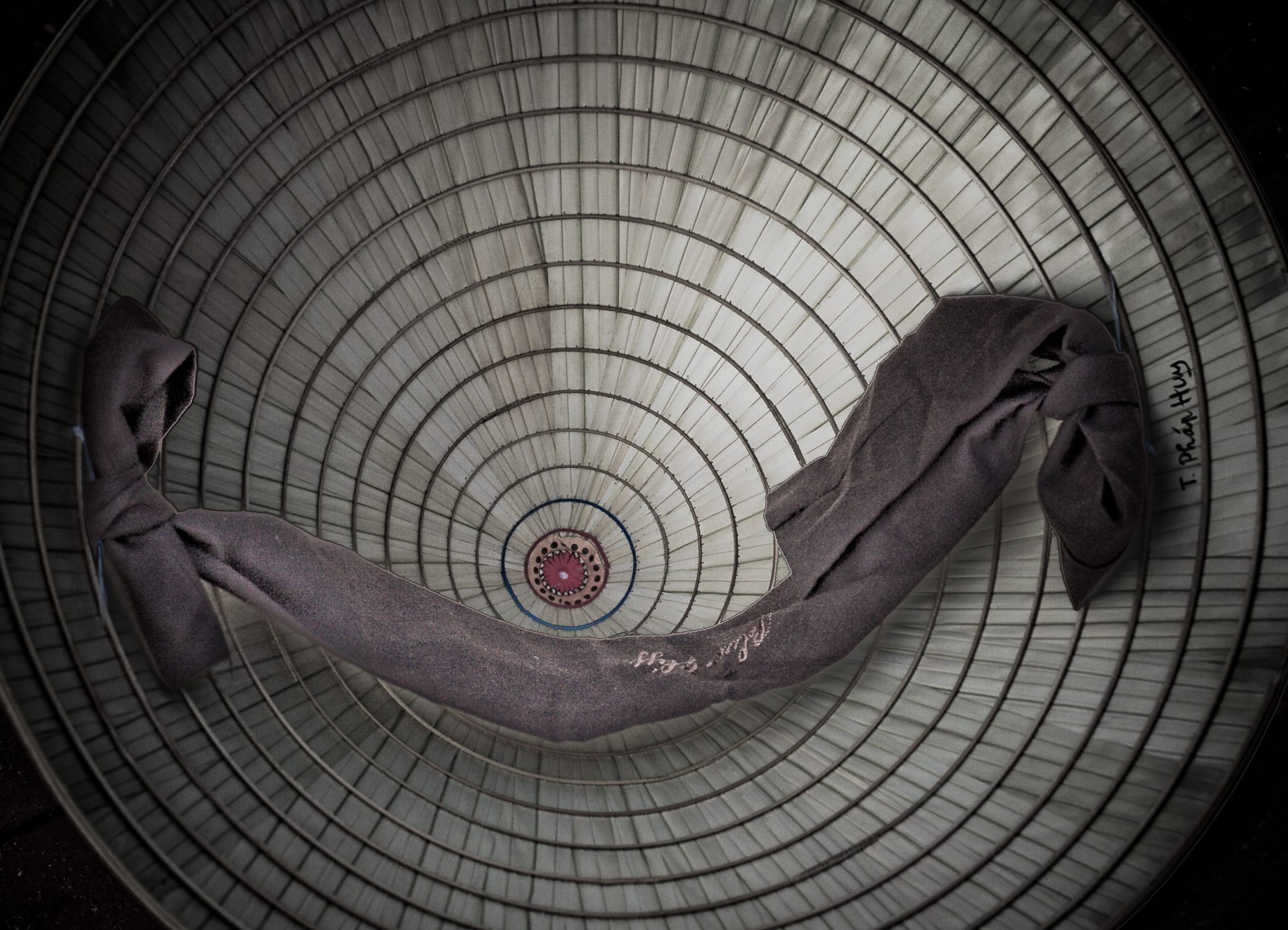

My plan of action was simple. Scheduled meditation was difficult for me, so I had to recognize that, and not be too hard on myself. I was spending a lot of time en route to different parts of the city to participate in open mics, jam with other musicians, explore, and commute to temp jobs. So, the sidewalks had to become my mountain paths, and the subway had to become my hermitage.

The reason people walk so fast in New York is not because the entire city is composed of Type A go-getters. It’s because one often has to walk long city blocks, over long bridges, or to and from subway stops. If you walk slowly here, it takes forever to get anywhere. I decided on a pace that would get me where I needed to go, but allow me to relax at the same time—something along the lines of driving on the highway at sixty or sixty-five miles per hour rather than seventy; just enough of an adjustment to take the edge off. At that pace, I could really enjoy my steps and take each one with all my love and compassion.

Breathing in, love and compassion flow from the soles of my feet.

Breathing out, I am happy.

Love and compassion.

Happy.

This meditation allowed me to smile to passersby and enjoy the city for the extraordinary place that it is. It inspired me to write positive music that deepened my practice, instead of turning to laments and despair.

Time on the subway became a time of deep practice for me as well. Once I found a job, I had to commute forty to fifty minutes each way, and wanted to make sure that I was alive during that time. I always had a book about the practice with me, and I often carried my Five Mindfulness Trainings certificate too. On the subway, I would enjoy my reading for a while, then stop, breathe, and look at the people around me. It was easy to see what a wonderful, extraordinary situation I was in: people from all nations, cultures, and religions packed into a small space together. With this new perspective, I was constantly amazed at how courteous people were—giving seats to the elderly, helping people onto trains, making space for others. There are many places in the world where this doesn’t happen.

Many times I’ve heard Thich Nhat Hanh say, “At the airport, when they search you before boarding a plane, they are not looking for your Buddha nature—they are looking for your terrorist nature. We have to start to recognize our Buddha nature.” It was important for me to notice manifestations of Buddha nature in the city.

Sometimes I sat, closed my eyes, and meditated on my breath. I got in over an hour of sitting meditation every day, and just as much walking meditation (I almost always took the stairs at the workplace). The only other place in which I had that much time to practice was at the monastery.

In the spring of 2008, my worldly situation hadn’t changed a lot, yet I was much happier. Practicing mindfulness had allowed me to transform New York City in my mind, so I was now able to walk in a city that was a beautiful practice center. At that time, I was studying Thich Nhat Hanh’s book, The Diamond That Cuts Through Illusion. Reading the text helped me achieve a lot of insight into the nature of interbeing, and the way we erroneously define our world. In the Diamond Sutra, there are ideas akin to: A tree is not a tree; that is why we call it a tree. After some meditation, I took a tree is not a tree to mean that a tree is the whole cosmos, composed of awakened nature. We call it a tree because we are under the illusion that it has a separate self. But like everything else, a tree is of the nature to be both birthless and deathless. With the teachings of the Diamond Sutra in my heart, looking at the faces in the subway car became even more wonderful because I felt more connected to my community.

My Brother’s Presence

On May 28, I got a phone call in the middle of the night with the news that my brother, Jason, had died. He was thirty-seven years old. In a hotel in Elko, Nevada, where he worked as a dentist, he had run up three flights of stairs to avoid being on a full elevator. He then bought a drink from a vending machine, turned from the machine, took a few steps, fell forward with his arms hugging his chest, and died. We later found out that he had died from an overdose of Demerol.

My family went through a complex process of mourning. And while Jason was the sibling to whom I felt closest, I am sure that my suffering was reduced because I entered it meditating on interbeing and our birthless and deathless nature. When I saw my other siblings and cried, I wasn’t always crying because Jason wasn’t there with us. Sometimes I cried because I was so happy to be in the presence of my family. Now, many months later, much of my family is still sometimes crippled with despair and sadness. But, because of my practice, I feel very in touch with my brother and feel his presence in all things when I am mindful. In fact— and I know this may sound strange—his death feels to me like he made a decision to move forward with his life.

Everything’s in Everything

I returned to Deer Park in the second half of December, 2008. I’d achieved my goal of deepening my practice in New York City and now felt I had to be in a quiet place to make sure I wasn’t in a state of denial about my brother’s death.

During my retreat at Deer Park, we were put into groups for Dharma discussion. I told the group about my experience with the Diamond Sutra and my brother. There was another man in the group—I’ll call him “H”—who had also lost his brother the year before, and still appeared to be in a lot of pain. The next day, as the Sangha walked among the sage and boulders of the surrounding mountains, I thought to myself, Jason is not Jason. That’s why we call him Jason. “H” was walking ahead of me, and he immediately stopped and turned around. He smiled and gave me a great big hug that pushed my hat askew and stopped the long line behind us.

We walked to an open space where we all sat on boulders and ate our lunch. I smiled, remembering a conversation I once had with Brother Phap Dung, the abbot of Deer Park, about being at the monastery. “Here,” he said, “when you need a brother or sister, a brother or sister is there for you. When you need a mom, a mom tends to appear.”

A simple, childlike painting that Cameron made hangs in our bedroom in New York. It’s a large group of people, all colors and sizes, each with a heart in their chest, sitting under a yellow sun and torn-paper sky. If you look closely, you can see that the little clouds are words torn from a dictionary: we…all…have…a…beating…heart…in…our…chest. On Christmas Eve, I played a song to the Sangha gathered in the meditation hall at Deer Park. I looked at all the faces there—the children, parents, brothers, sisters, monks, and nuns—and told them how much they reminded me of the painting. The song was called Everything’s in Everything, inspired by Cameron’s painting, The Diamond that Cuts Through Illusion, and the reality of interbeing.

We all have a beating heart in our chest

There is nothing separating East and West

We are breathing in and out the same sky

We are looking at each other with new eyes

Everything’s in Everything

Everyone’s in Everything

Everything’s in Everyone

Everyone’s in Everyone

I love all the people passing by me

I love all the buildings in the sky of the city

I know all the forests are my lungs breathing

I know all the oceans are my blood streaming

Peace is resting in the palm of our hands

We can see it in a tiny grain of sand

Breathing in and out we smile to the moment

Everything’s in everything and always flowing

Nate Metzker, Compassionate Sound of the Heart, is a novelist and musician who lives in Brooklyn and teaches at the McCarton School for Children with Autism.