By Sister Annabel, True Virtue

Life on the Farm in England

I grew up in a part of England near the West Coast that enjoyed the effects of the Gulf Stream. Although temperatures did fall below freezing sometimes and even snow fell, it was not cold like New England is. My mother gave birth to me in a house that had no electricity. The kitchen had a coal stove that mother tried to keep alight twenty-four hours a day.

By Sister Annabel, True Virtue

Life on the Farm in England

I grew up in a part of England near the West Coast that enjoyed the effects of the Gulf Stream. Although temperatures did fall below freezing sometimes and even snow fell, it was not cold like New England is. My mother gave birth to me in a house that had no electricity. The kitchen had a coal stove that mother tried to keep alight twenty-four hours a day. The living room had a log fire that in winter was lit in the late afternoon. No other room had heating, although the kitchen stove provided hot water for all our needs.

Conservation of heat was something we learned from an early age. As soon as outside temperatures began to fall in the late afternoon all doors and windows were closed. As soon as night fell all curtains were closed. Father was strict about this and supervised it. Even now he continues to be responsible for conserving heat in the small house where he lives with my mother. In this way the precious heat of the sunshine that has accumulated within the four walls of the house is not lost.

Our water came from a spring at least half a mile from the house. It was pumped by an engine driven by a windmill. From an early age we learned not to waste water.

My father had a small motorcar but we did not use it so much. Our house was on a hill above the sea. We walked to the village or took the ferry boat across the estuary to the nearest town. We produced very little refuse. There was the compost pile, an occasional bonfire, and for metal that the scrap iron man did not take, there was an old quarry. In all the Plum Village hamlets there is always to be found a brother or sister who gives much thoughtful and caring energy to the work of recycling.

When I was a child recycling was not a concept that occurred to my family because we had so little to throw away. When I lived in India the same was true. If somehow you came across a plastic bag you would use it until it was falling apart. All plastic and metal containers were reused. If you went to the market and the produce you bought had to be wrapped in paper it would be paper that had already been used.

Since I was born not long after the Second World War, my teachers and parents, as well as the parents of my school friends, were very strict about not wasting food. Children were not allowed to serve their own food. The appropriate amount was put on my plate by an adult or a senior school prefect. The more lenient among these elders would ask for my input about the quantity I received.

I could say small if I wanted a small helping. Whether I had had a say in what was on my plate or not, it all had to be eaten and I could not stand up and leave the table until my plate was empty.

Nearly all of what we ate was produced locally: either in our own garden or by local farmers. We had an apple orchard that had been planted by my great-grandfather. It had many rare and wonderful kinds of apples, varieties that it was never possible to buy. Every tree was a different variety. The earliest fruits ripened in July and the latest in October. Preserving summer fruits and vegetables for use in the winter was a common practice. Tangerines were a once-a-year treat at Christmas time.

The longevity and good health of my parents can be largely attributed to this simple way of life that involved spending a significant amount of time outdoors. My father was a farmer; my mother looked after the vegetable garden, the hens, and the orphaned lambs (sheep often die in childbirth), made butter, and worked in the fields at harvest or planting time.

Paper Napkins, Organic Food

When I was a child paper serviettes were a treat for birthday parties; otherwise cloth napkins were always used. When I first came to Plum Village we used paper napkins for tea meditation. In order to save forests we carefully cut each napkin into four parts and each person had a quarter of a napkin. Then we thought that even a quarter of a napkin was an unnecessary waste so we provided each person with a cloth napkin to bring to tea meditation, to launder and use while in Plum Village. Many people lost their napkins or forgot to bring them to the ceremony, so we changed to leaves. Those preparing the tea ceremony collect, wash, and dry the leaves carefully, and then place a biscuit upon each leaf.

The monastery cellarer does not provide paper napkins for everyone to take at meal times. When we are on tour with Thay, some brothers and sisters will take one paper napkin and divide it in four or use it successively for several days.

Eating organically is something that as a sangha we can do, but if we are to keep within our budget allowance it would mean a significant simplification of our present diet and the ability to eat a more limited variety of foodstuffs. We would need to make our own bread, tofu and soya milk from organic ingredients. It would mean accepting only one protein, one carbohydrate, and whatever other vegetables and fruits might be available at every meal.

My main reason for eating organically is not so much that I do not want to ingest inorganic food, as I want to support farmers who are doing their best to protect the planet. It would mean restricting ourselves in the main to foods that are in season, which is one thing in California, but another thing in New York.

Simple Living

In Plum Village we always dry our clothes on the line outside or in the laundry room inside. When we first came to Vermont we were visited by a delegation of anti-nuclear protesters from Texas. They told us that the nuclear waste from the nuclear-powered electricity stations in Vermont was buried in the Texan desert. They left behind a number of clothes pegs as a reminder to us that we should not use the clothes dryer, the largest consumer of electricity.

Simple living was the first way of life I learned. To me it is very natural. I realize that to many people, especially those who have spent a large part of their lives in the United States, simple living is not so natural. For every household to have electricity and running water seems reasonable for our time. Can we be very sparing in their use in order to reverse the trends that are destroying our environment?

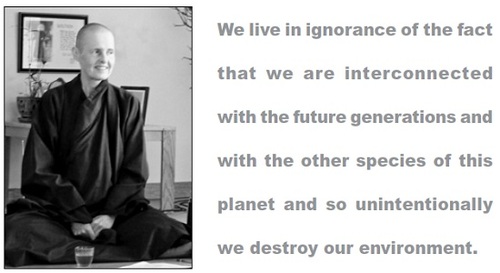

In the Sutra on Knowing the Better Way to Live Alone, the Buddha asks the monks: “How can we live without being carried away by the present moment?” The reply is deep. We are not carried away in the present moment when we are not caught in the idea that this body and consciousness are mine. We live in ignorance of the fact that we are interconnected with the future generations and with the other species of this planet and so unintentionally we destroy our environment. If we are not mindful when we turn on the light we may turn on a light that does not need to be turned on or fail to turn it off. The same is true of turning on the air-conditioning or the heating.

Once we are aware of the long-term effects of simple actions, such as turning on and off a switch, we are much more careful. Even if we only recite the gatha as we turn on the light it already brings enough awareness into the action to help us remember to turn it off later or just to turn on the number of lights that are needed.

Thay’s personal life is an example of simple living. When I used to translate from Thay’s manuscripts, I noticed that Thay wrote in the margins. I learnt to do the same. I keep letters and other sheets of paper that have not been covered in writing for scrap. In the United States the amount of scrap paper I collect is enormous. Finally it takes up too much space and I have to put it into the recycling bin.

I do not regret technological advance when it reduces real suffering, but I regret an unnecessarily wasteful way of life. I ask myself why I cannot live as simply as I did fifty or more years ago, when I was quite happy and comfortable enough.

A Necessity for the Future

The fourfold sangha can help to lead the way in ecological living rather than being pulled along by the collective consciousness. We have the practices of mindful breathing, walking, and the little gathas that help us be aware of our everyday actions. We also have the wonderful teachings of the Vajracchedika Sutra that help us to look deeply into the fact that the human species is not separate from all other species whether we call them animate or inanimate.

Deer Park has a project to introduce solar energy that has begun to be realized. It was suggested by Thay many years ago. Already in Blue Cliff Monastery we have had the offer of an environmental architect to give us his services to make it possible to use alternative energy sources in the future. Brother Patience with great patience every day takes care of the trash that can be recycled. One of the sisters is planning the area for drying clothes.

It is wonderful to know that simple living is not a thing of the past but a necessity for the future. In the past, as now in many parts of the world, we lived simply because the material resources were not available for us to live any differently. Now we have the material resources and it is our conscious choice to use them wisely. We do not have to turn the electricity off one day a week but we can make the conscious choice to do so for the sake of our environment now and for the generations that are to come. From being Homo Sapiens (the clever human) we become Homo Conscius (the aware human).

Sister Annabel, True Virtue, is abbess of Blue Cliff Monastery in New York State. Sister Annabel was one of Thay’s first students in the West; the Mindfulness Bell is serializing her story.

Suggestions for Ecological Living

- Global warming is a fact that makes us feel very sad but we do not fall into despair because we know that there is something we can do as a sangha or an individual to reduce it. Examples include a no-electricity day, a no-car day, and a no-water-from-the-faucet day once a week. When we practice in this way, not only can we reduce global warming, but we also feel closer to those who live in underdeveloped and developing countries. Until I find the skillful means to encourage the sangha to which I belong to live in a more environmentally friendly way, I have to practice a mind of non-blaming, non-condemning, and non-criticizing. I have to be aware of these mental formations as and when they arise and embrace them so that I do not suffer and make others suffer.

- It is not safe to protect the material environment without protecting the spiritual environment. Environmentalists are in real danger of falling into this trap.

- I can look deeply to see the individual and collective karma that have put me into an environment that is not protecting the planet to the degree that I should wish.

- I can be satisfied with being an example of ecological living, using the occasions I can to help others protect the environment more.

- I do not allow myself to be a victim. This means I do not passively accept what is happening, saying ‘so much the worse for all of us’ and waiting for someone else to come along and rescue me. Instead I am always ready to contribute my understanding.

- Sangha harmony, brotherhood, and sisterhood are essential for the future of our planet. It is not true that protection of the material environment comes first and brotherhood second. The two should go along together, hand in hand. To halt the environmental destruction we need a collective awareness that is only possible because of brotherhood. I continue to take refuge in the sangha, being an element that can hold the environmental awareness along with others, although it may only be a minority. Once I cease to take refuge in the sangha there is almost nothing I can do to save the environment, be it material or spiritual.

- I am aware that there are wasteful ways of living that do not look wasteful on the surface. For example, even though I eat every grain of rice on my plate I eat unmindfully without nourishing the spiritual dimension of my life. In this way I waste the food because it does not contribute anything to my spiritual path. I must always be humble about my own shortcomings.

- The practices of mindfulness as taught by the Buddha are essential for diminishing the destruction of the environment. It is only by being aware of my daily actions and habit energies that I can truly protect my environment. Once I go on automatic pilot1 I am a victim of the collective consciousness and its ignorance.—Sister Annabel, True Virtue

1 This word is used by Thay to say that we use the habit energies stored in the store consciousness to perform repetitive daily actions such as driving, brushing our teeth, turning on the tap, walking, etc.; we are not aware with the mind consciousness of what we are doing.