By Judith Toy, Richard Brady in February 2007

The Garden at Night Burnout and Breakdown in the Teaching Life

By Mary Rose O’Reilley Heinemann

2005 Softcover, 96 pages

Reviewed by Richard Brady

In case she’s not already known to you, it’s my happy task to shine the light on one of Buddhism’s hidden Dharma teachers,

By Judith Toy, Richard Brady in February 2007

The Garden at Night Burnout and Breakdown in the Teaching Life

By Mary Rose O’Reilley Heinemann

2005 Softcover, 96 pages

Reviewed by Richard Brady

In case she’s not already known to you, it’s my happy task to shine the light on one of Buddhism’s hidden Dharma teachers, Mary Rose O’Reilley. O’Reilley is a poet, a teacher of English and rhetoric, and the author of books that include The Peaceable Classroom, Radical Presence, and the autobiographical The Barn at the End of the World. Her new book, The Garden at Night: Burnout and Breakdown in the Teaching Life, is in reality a series of four very personal Dharma talks on engaged practice. In this short gem of a book O’Reilley calls on the wisdom of teaching from Thây, the Bible, and a panoply of writers and friends to inform her practice as an English department member in a Midwestern America parochial college. As the title suggests, Garden is a book written in response to suffering, suffering brought on by departmental meltdown, deaths of students, and inhospitable working conditions.

The lessons O’Reilley works with are ones that will be familiar to mindfulness practitioners. Each person constructs his or her reality. Your awareness of your authentic self is easily lost in busyness and your struggle to do it right in the workplace, even just to survive. Receive whatever comes your way as an opportunity for practice. Don’t get caught in characterizing your experiences as “good” or “bad”; they’re just your experiences. Change your relationship to time: live slowly enough to encounter life with mindfulness. This makes freedom possible, your one true freedom, which is to be authentic.

In my experience, these changes are easy to articulate and challenging to accomplish. O’Reilley agrees. She receives a great deal of support from regular times of retreat and from spiritual friends. When the next suffering comes along, hers or that of someone close, to test these lessons, her supports make it possible for her to remain present to the suffering. And it is particularly in the contemplation of suffering that O’Reilley finds the impetus for personal transformation and prophetic witness.

For readers who wonder how to grow in the absence of major suffering, O’Reilley describes practice with some of her personal koans and questions. Searching for guidance on how to carry on in her profession, she ponders the tension between Jesus’ advice to “Be therefore wise as serpents and harmless as doves” (Matthew 10:16) and the imperative to be herself. Recognizing her inability to control or even truly understand what her students are learning, O’Reilley asks herself the “painful” question, “What did I just learn?”

Suffering is suffering. So whether or not you’re an educator, you’ll likely resonate with the reality O’Reilley describes. This is the book to share with friends who wonder what mindfulness practice has to do with life. More than that, it’s a wonderful reminder and teacher for us all. Approach this book with an open heart. Its humor, its humility, its poetic truths will water your seeds of compassion and hope.

Eastern Wisdom, Modern Life Collected Talks 1960-1969

By Alan Watts

New World Library, 2006 245 pages

Reviewed by Judith Toy

Our beloved hippie icon, the late Alan Watts, is back. Thanks to his son, Mark Watts, keeper of the family archives (see www.alanwatts.com), a new compilation of his radio and TV broadcasts and recorded public lectures is out in book form: Eastern Wisdom, Modern Life, Collected Talks 1960-1969. With its vintage excess of language and Wattsian wit, this is another exciting collection from the British-American philosopher and theologian who beguiled multitudes of flower children, setting many of us on the Buddhist path with manuals such as The Spirit of Zen, Square Zen Beat Zen, and The Way of Zen.

As a small child, I remember losing sleep one night because I was imagining the “forever-ness” of death. I envisioned eternity as a scary, endless corridor of doors where one door always led to another. One of the great things for me about reading Alan Watts as a young adult was that he knew his young readers still harbored such fears. From the new collection:

The idea of nothing has bugged people for centuries, especially in the Western world. We have a saying in Latin, Ex nihilo nihil fit, which means “out of nothing comes nothing.” It has occurred to me that this is a fallacy of tremendous proportions.... It manifests in a kind of terror of nothing, a put-down of nothing ... such as sleep, passivity, rest, and even the feminine principles.

And from another essay, “Our fascination with doom might be neutralized if we would realize that every new doom is just another fluctuation in the huge, marvelous, endless chain of our own selves and our own energy.”

He persistently sees the universe as a deep and harmonious whole. Calling on his complex knowledge of history and quick deductive reasoning, Watts reassures:

But to me nothing—the negative, the empty—is exceedingly powerful... [Y]ou can’t have something without nothing. Imagine nothing but space, going on and on, with nothing in it forever. The whole idea of there being only space, and nothing else at all is not only inconceivable but perfectly meaningless, because we always know what we mean by contrast.

Where to begin?! I was like a kid in the candy store with his new book. His subject matter covers the gamut from “Divine Alchemy” to “Religion and Sexuality,” frolicking through “Philosophy of Nature,” “Swimming Headless,” and “Zen Bones.” Although these essays show only a handful of the talks Alan Watts gave in the sixties, they embody the whole, highlighting a distinguished career that reflected the counterculture of the sixties and paved the way for the Western flood of interest in Far Eastern traditions that has not abated since.

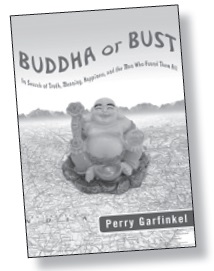

Buddha or Bust In Search of Truth, Meaning, Happiness and the Man Who Found Them All

By Perry Garfinkel

Harmony Books, 2006 Hardcover, 320 pages

Reviewed by Judith Toy

In an inquiring-mind style that Perry Garfinkel calls Zen journalism — “a kind of karmic random access, driven by Google...ramped up by coincidence and luck, inspired by jazz improvisation, necessitated by an incurable case of procrastination” — he circles the globe looking for manifestations of engaged Buddhism. Expanded from a piece for National Geographic, this book describes the author’s nine-nation pilgrimage with visits to major Buddhist shrines and dharma teachers, including Thich Nhat Hanh.

Through the internet, Garfinkel locates Order of Interbeing’s Shantum Seth, who becomes his tour guide in Bodh Gaya, India, where Shakyamuni Buddha found enlightenment. At Bodh Gaya, the sensory bombardment he describes is like a synthesis of Garfinkel’s whole trip: “The deep voices of a hundred Tibetan monks, their chanting amplified by tinny speakers, ...wide-eyed American neophytes, ...stern Japanese Zen priests, ...curious Indian Hindus, ...ebullient Sri Lankans.” Surrendering to his senses, Garfinkel does find peace in Bodh Gaya.

Some of the koans he carries with him around the world are: Why the meteoric rise of Buddhism in the west? Why now? How is it that monks can enter politics and Buddhists be at war in Sri Lanka, “a country hemmorrhaging from within.”? What would the Buddha think of the Taco Bell TV ad touting “enchilada nirvana,” the Madison Avenue-ization of the dharma? As compelling as these questions are, the author’s honesty is equally so. He tells of the headiness of being granted a one-on-one interview with His Holiness the Dalai Lama. He compares the austerities of Japanese “marathon monks” to the asceticism rejected by Buddha. He wonders if ritual as practiced in some Buddhist cultures may cancel out its original meaning.

At a Vietnamese-speaking retreat at Plum Village, where he felt “like a fish out of water,” Garfinkel managed to sit with his “mishigas,” fall in love, and have a sudden gestalt of compassion through listening to a Vietnamese victim of war torture. Finally at Plum Village, the author has a revelation when he asks Thây, after a dharma talk on relationships, “Aren’t there more important issues to discuss than relationships?” Thay answers rhetorically, “Such as war, violence, death, economic problems, terrorism?” Misunderstanding, explains Thây, begins in the microcosm, between two people. It creates fear, and fear creates violence in the world at large. “Peace in myself, peace in the world,” is indeed a Plum Village mantra.

Does the author find truth, meaning, happiness? Yes and no. Summing up his fantastic voyage, Garfinkel ironically quotes eighteenth-century Japanese poet Ryokan: “If you want to find the meaning, stop chasing after so many things.”