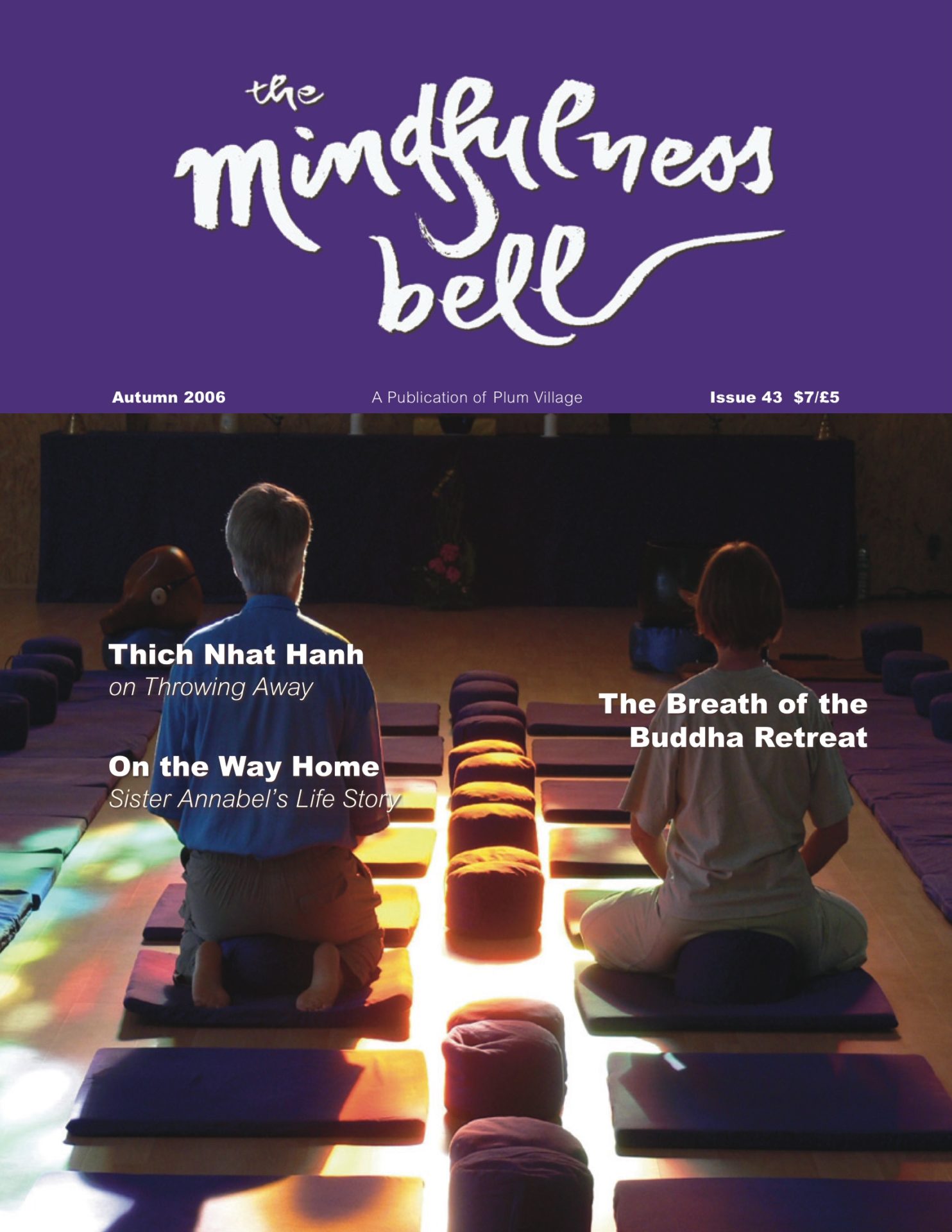

The Energy of Prayer

How to Deepen Your Spiritual Practice

By Thich Nhat Hanh

Parallax Press, 2006

155 pages

Reviewed by Judith Toy

When Thich Nhat Hanh tells us, “You are a cloud,” this sounds very poetic. What he means is that our bodies contain cloud elements, a fact that science cannot dispute. Taking the same no-nonsense approach to prayer in his new pocket-sized book on the subject,

The Energy of Prayer

How to Deepen Your Spiritual Practice

By Thich Nhat Hanh

Parallax Press, 2006

155 pages

Reviewed by Judith Toy

When Thich Nhat Hanh tells us, “You are a cloud,” this sounds very poetic. What he means is that our bodies contain cloud elements, a fact that science cannot dispute. Taking the same no-nonsense approach to prayer in his new pocket-sized book on the subject, our dhyana master begins with the facts. In the book’s introduction, Larry Dossey, M.D., writes that there are currently 200 controlled experiments “in humans, plants, animals, and even microbes” suggesting that the energy of prayer can affect another individual or object, even at great distances.

But does prayer really work? In the first chapter, Thây offers readers the story of a double healing through prayer—a boy’s skepticism is healed at the same time that a woman’s brain tumor disappears. Reading this book proves what I, too, know, as I once healed completely from fibromyalgia and stomach ulcers through prayer. I have been present in the dharma hall when Thây requests that we “send energy” to someone who is sick or dying. We do not ask for the person to be healed; we simply send our concentrated, loving energy, sometimes long distance. And we know this has its effect, just as the moon has an effect on the earth.

Prayer is not meant to be a wish list; it’s a state of being. The secret is to pray with a mind of no attainment. While our teacher gives us many classic chants and prayers to choose from, as well as an appendix with exercises in meditation, he tells us that prayer can be realized not only in words, but in action. This is important especially for those who think they need “an answer” to prayer. The prayer itself is the answer. Prayer transforms the pray-er.

One of Thich Nhat Hanh’s greatest pedagogical gifts to the world has been tying East to West, Judeo-Christian to Buddhist practice. We need not drop our Judeo-Christian roots; our mindfulness practice makes us more sincere Christians, more deeply reverent Jews. In two of his watershed books, Living Buddha, Living Christ, and Going Home: Jesus and Buddha as Brothers, the author marries Christian and Buddhist practices. For me one of the most exciting chapters is Thây’s discourse on the Lord’s Prayer, which I’ve been praying for six decades.

Love is reflected in love. With “And forgive us our debts as we have also forgiven our debtors,” Thây exhorts us to pray in such a way that we “go beyond birth and death.”

What is prayer, then, but a raising of the mind and heart to God? And who is God but our very interbeing, the eternal flame that illumines everything, including the cloud. Our meditation and daily mindfulness practice is prayer. So prayer is a lightening and a lifting up. “We will lift her up [to God],” says the Christian. “We and God are not two separate existences,” writes Thich Nhat Hanh. I know this to be true.

Mindful Politics

Melvin McLeod, editor

Wisdom Publications, 2006

Paperback, 304 pages

Reviewed by Svein Myreng

In the introduction to Mindful Politics, editor Melvin McLeod writes, “This is a handbook, a guide, a practice book, for people who want to draw on Buddhism’s insights and practices to help ... make the world a better place.” A long-time Buddhist practitioner with a background in political science, McLeod has gathered 37 prominent Buddhist teachers, writers, and practitioners for this book.

At the core of mindful politics is the importance of stability and calm and how Buddhist practitioners can make this contribution to politics, especially in connection with anger and conflicts. In his essay, Roshi Bernie Glassman states: “I don’t believe in a utopia of non-conflict. Whatever you do is going to create conflict in some ways and peace in other ways.”

Also central to the book is Thich Nhat Hanh’s advice on understanding and compassion in all walks of life—familiar teachings to Thay’s students, but well worth re-reading. These are teachings of an uncompromisingly radical nature; just look with fresh eyes at a statement like “Compassion is our best protection.”

Other contributors bring perspectives from their own traditions, with Vajrayana and Zen perhaps a bit overrepresented. Buddhism is not monolithic. At times, however, the book’s perspective feels a bit too narrow, tipping the scale with people who are popular authors in U.S. Buddhism right now. For instance, I miss the fearless words of an Aung San Suu Kyi, or the old-time political commentary of Gary Snyder.

Especially interesting to me are the articles on racism and economy. Sulak characterises “free market fundamentalism” as “akin to other kinds of fundamentalism.”

Rather than GNP, Gross National Product, Jigmi Y. Thinley, Minister of Home and Cultural Affairs in Bhutan, suggests we use GNH, Gross National Happiness, as an alternative for measuring real weath. Thinley suggests four vital elements to GNH: “(1) sustainable and equitable socio-economic development, (2) conservation of the environment, (3) preservation and promotion of culture, and (4) promotion of good governance.” I would like to read more on these topics.

I write this review as a Dharma teacher, a father, and someone who wishes to make a positive contribution to the world. Though my wife and I try to live a simple, non-harming life and protect our son and ourselves from the greed-and-speed society, it is difficult. We neither wish nor are able to live in a cultural cocoon. We want to influence society, even in a small way. Mindful Politics is definitely helpful in this respect. It makes me think more deeply about aspects of my life and society.

Three Poetry Books

Reviewed by Susan Hadler

Something wonderful happens when we slow down and take the time to wake up to our bodies, our minds, and the world around us. We see things in the light of interbeing. We are able to touch the true nature of reality. The poets whose work is reviewed here devote themselves to noticing and connecting deeply with life in the present moment. They’ve put into words their experiences of delight and transformation and insight. It is a joy to find so many images that bring together the historical and the ultimate dimensions.

Fruits of the Practice

By Emily Whittle

Self-published, 2004

222 E. 5th Ave., Red Springs NC 28377

Soft-cover, hand-bound, 25 pages

The author of this beautiful earth-brown hand-bound book is a gardener of the heart and mind. Trained as a fine artist, primarily in book arts, Emily has taught all aspects of book making, and she brings her skills to the construction of this book. Her poems offer delicious fruit ripened in the sunshine of awareness. Playful images and fresh connections abound, this one from “A Break in the Weather”: “After seven days of rain, dawn serves up a new day, round as an egg, sunny-side up,” and this, the opening line of “Zafu”: “My church is a round cushion.” Still other poems astonish us with reality, as in the last line of the poem entitled “You Asked About My Anger”: “Even with remorse it takes a long time before the birds come back.”

Most of all, the poems live as stories of life on the path of awareness, bright with surprise and clarity of insight and transformation. Here, from the first poem in the book, titled “Origami”:

Watch this! A square of paper folded on itself becomes a crane. . . When my spirit lies flat and limp, a lost scrap under my heart’s table, I must bend and stretch, touching all my corners. Aha! I see the tiger emerging already!

Bird of the Present Moment

By Pamela Overeynder

Plain View Press, 2005

Soft cover, 79 pages

A sense of belonging, “each thing to every other,” infuses the poems in Bird of the Present Moment with the beauty and truth of nature; grasses “flowing nowhere in great waves,” and oaks that “go gladly with the wind,” and this from “Hillside Theater”: “The sun takes its final bow and melts down into the rock. Then like a child who doesn’t want to sleep, it peeks upward just before the chill.”

There are poems that declare the narrator’s delight in simple things like swimming “comfortable as a fish” and in brushing her teeth “to the rhythmic sound of crickets.” Other poems, like “Bird Island,” state in elegant simplicity what the poet knows from connecting deeply with herself and the present, in this case terrifying, moment:

What slowly seeps into both of us during this longest night. . . is the irreducible and indestructible truth that the present moment is all the life we have.

Gateways: Poems of Nature, Meditation and Renewal

A Self-Guided Book of Discovery

By Sylvia Levinson

Caernarvon Press, 2005

35 pages

Each of the 15 poems in Gateways is like a dharma sharing that opens mind and heart. The poems come from stopping, Levinson tells us in the introduction, and attending to life around and within. A withered fern offers a “meditation of resting.” During walking meditation a young monk “places a finger below a single droplet [and] waits for it to fall.” Sitting in the quiet of early morning, a finger traces “a sifting of pollen that has settled like powered sugar on the blue bowl”; ordinary experiences brought to life with attentiveness and shared as poems.

The poet is our guide to what may lie unnoticed, yet is alive within us right now. She does this by introducing each poem with a short prose description of the discovery that inspired the poem. Before “What Feeds My Soul,” she writes, “Things all around us can give moments of pleasure and peace.” Here, a fragment:

Yesterday, it was the little redheaded bird that lit on my balcony and poked its beak among the sweet alyssum.

Last month, the bowed head of a classical guitarist suspended over his instrument, waiting as the final note disappeared. . .

After each poem, the author poses questions. For this poem, she asks the reader, “What ‘something’ takes you out of the routine and mundane and feeds your soul?” Opposite each written page is a lined blank page, space for the reader to try writing poems of her own.