By Sister Dang Nghiem in October 2006

When I close my eyes, I see hundreds of little eyes looking at me: round, dark, innocent eyes, eyes opened wide. They wrench my heart and force me to seek deeper understanding of my path.

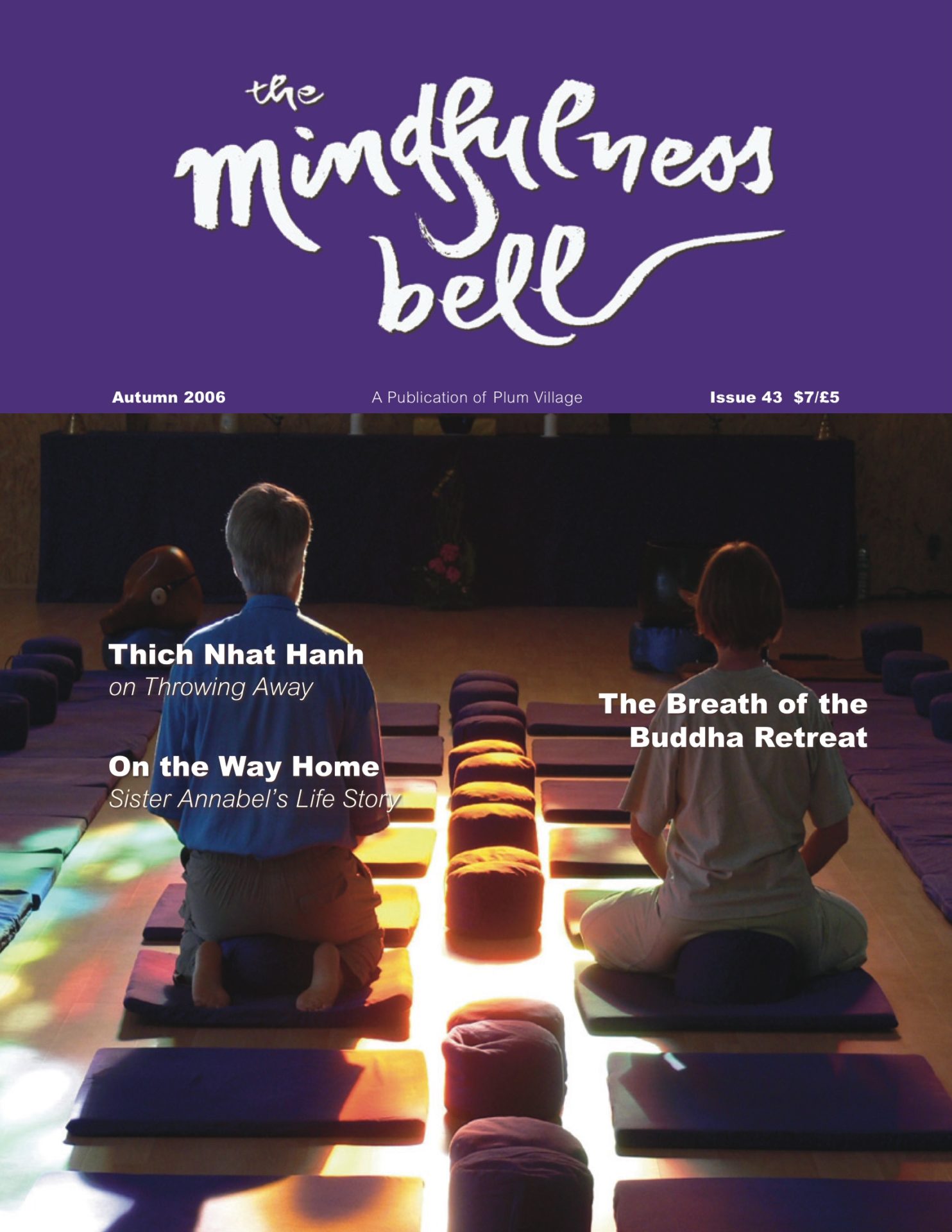

Therese came to visit our Understanding and Love Program in the highlands of South Vietnam. We organized a tea meditation at Prajna Temple on the night of her arrival to celebrate her visit and the visit of one of our elder sisters.

By Sister Dang Nghiem in October 2006

When I close my eyes, I see hundreds of little eyes looking at me: round, dark, innocent eyes, eyes opened wide. They wrench my heart and force me to seek deeper understanding of my path.

Therese came to visit our Understanding and Love Program in the highlands of South Vietnam. We organized a tea meditation at Prajna Temple on the night of her arrival to celebrate her visit and the visit of one of our elder sisters. The meditation hall was packed with over 250 monks, nuns, laymen, and laywomen.

Our Venerable Abbot spoke warmly to welcome the visiting sister and Therese. He told the history of our Prajna monastery (“Prajna” means “understanding”). Around 40 years ago, inspired by Thây’s teachings that he had read in Fragrant Palm Leaves, he and seven other young novices had the aspiration to continue Thây’s teachings and practices of engaged Buddhism in the highlands of South Vietnam. They built their first hermitage in what is now known as An Lac Temple (Temple of Peace and Happiness). That temple gave birth to seven other temples including Prajna, the most recent, established in 1998. Except for An Lac, the temples are situated in the remote areas of the highlands where the aboriginal K-ho people live and the poor people from North Vietnam have come to resettle.

Over the years, our Venerable Brother and his monastic disciples lived with and supported the people in these underserved communities. They established a school following the model of the Understanding and Love Program begun by Thây’s social workers in the 1960s.

When our Venerable Brother wanted to expand the school program, he went to Plum Village to ask Thây for support. For the eight years that followed that visit, Thây’s lay students trained through the School for Youth and Social Services have worked with the Venerable to establish 39 kindergarten schools for children in the distant areas of the highlands.

The next morning we all got in a van—our Venerable Brother, Therese, four social workers, the driver, and me, Therese’s translator.

Noble Veterans of the School for Youth and Social Services

The four social workers who accompanied us were young men in their twenties when they joined the School for Youth and Social Services (SYSS), established by Thây. Now they were all in their sixties. In the 1960s they had gone to war zones and worked together with the villagers to build bridges, create makeshift classrooms, and establish health clinics.

“Over three hundred social workers had graduated from the School for Youth and Social Services,” they said. “Thây continued to provide us guidance even after he went to Europe and the United States to call for a stop to the war in Vietnam. However, when the communists took over Vietnam, all of our social works were forbidden. We lost contact with Thây for fifteen years!

“After contact was re-established, we began to do social work again. Now, there are only a few more than 30 active social workers working throughout the three regions of north, central, and south Vietnam.”

I asked the men what fueled their minds of love after all these years. “It’s our love and loyalty to Thây,” one replied, and the three other social workers nodded in agreement. “It’s also the practice of the Dharma that nourishes us. We certainly would not be able to continue this work if we did it for the money.” (They receive every month from Plum Village an equivalent of less than $100 dollars.)

Fresh as the Dew, Solid as a Mountain

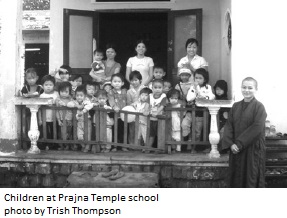

The first of the kindergarten schools we visited was not far from our monastery. I hesitate to call these locations schools, because they are just one to three rooms (each room about 3 by 4 meters), one small kitchen, and a toilet (squatting style). Most of the schools stand isolated in a field of tea plants; some are built adjacent to the house of the people who have donated the land.

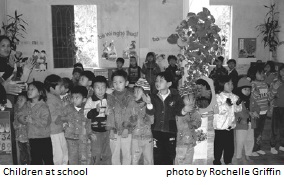

As we walked to the door of the first school, the children stood and joined their palms into lotus buds to greet us. “We respectfully greet Thây” (to our Venerable Abbot). “We respectfully greet Su Co” (Su Co literally means Miss Teacher, which referred to me, a Buddhist nun). “We respectfully greet our aunts and uncles” (this to the social workers and Therese). The children all looked at us with their big eyes, then quietly returned to their places. There were no tables and no chairs. Thirty to forty children sat on the floor next to each other along the walls of the room. At some schools, the floor had ceramic tiles, but at the more remote locations, the floors were made of bare cement.

Therese and I walked into the room and sat down with the children. Their teacher led them in a song: “Here is the Pure Land. The Pure Land is here. I smile in mindfulness and dwell in the present moment....” Then she started another song: “Breathing in, breathing out. Breathing in, breathing out. I am blooming as a flower. I am fresh as the dew. I am solid as a mountain. I am firm as the earth. I am free.” The four- and five-year-olds sang enthusiastically with their hands gesturing for flowers and mountains. The very little ones just lip-sang or sat wide-eyed in silence.

Keeping the Children Safe and Fed

At each location, Therese asked why there was a need for our Understanding and Love Program. The teachers and social workers explained that the local government only provided primary schools; there were no schools for toddlers. In addition, the parents had to pay for school fees and daily meals. Since most of the people in these regions work on tea and coffee plantations, either working for themselves or for the Taiwanese companies that have 50-year contracts for use of the land, they are too poor to send their children to the government school. Many parents had to leave their children at home so that the parents could go to work in these plantations. The children had many accidents at home by themselves. These were the reasons the parents came together and petitioned our Venerable Abbot for a school for their toddlers.

The families promised to take turns offering a room in their house for the school; often the woman in that family also offered to be the teacher for the school. Eventually the parents planned to put together enough money to buy land for a real school for their children, but when the parents cannot raise enough money for a school, the Understanding and Love Program helps them buy the land, purchase the materials for the school building (the parents work together to build it), pay the teacher’s monthly salary, and feed the toddlers two times a day.

The Joy of Giving

In some locations, the parents donate the land for the school. I met a woman who had offered the small piece of land that her family owned for a place to build a school. The Understanding and Love Program has not yet collected enough money to build it, so she was also allowing the school to meet in her house. Her house has only two rooms and it is small and shabby. I was too curious not to ask her, “Your husband and you are so poor. Why did you not sell the land that you have? Why did you donate it to the school?”

She exclaimed, “We would never sell the land!”

“Then why did you donate it?”

“Grandfather Monk (referring to Thich Nhat Hanh) and the monks and nuns do charity work for us. This is my contribution to the charity work,” she said.

My heart sank into a deep silence.

Her two children were helping with the school program. I asked the younger one if it was annoying that so many children were in her house. “Not at all, respected Su Co,” she replied.

“Does it bring you joy then?” I asked.

“Yes, very much so, Su Co,” she answered with a smile. “What do you do to help?”

“When I come back from school, I help my mother wash the children’s hands and feet,” she said.

I turned to her older sister. “Do you help your mother with the children, too?”

“Yes,” she answered quietly. “Are you still in school?”

“No, Su Co. I stopped going to school after fourth grade.” “Do you wish to go to school?”

“Yes,” she replied quietly.

“Does it make you sad that you cannot go to school?”

She simply looked down to the floor; her face turned pale. I stroked her unkempt hair and breathed mindfully. Later, as we walked out of the woman’s house, Therese said to me, “It’s so sad that the mother’s salary as a teacher is not enough to put her own children in school!”

Serving the K-ho People

We visited a school of the aboriginal people of K-ho. The teacher was 24 years old. She had received a scholarship to go to a university in the city, but she chose to stay and teach her own people. She taught a night class to teenagers and adults for a number of years, and thanks to her, illiteracy was eradicated in her area. During the day, she took care of toddlers and taught them how to speak, read, and write in Vietnamese. Each year, she would take the ones who had just turned six to the public primary school, then for a week to ten days, she walked with them to their new school, staying in class with them as they got familiar with the place and became less frightened. Then she returned to her own preschool class. She was the only teacher to thirty toddlers. Another woman helped cook breakfast and lunch for the children.

We went deeper into the forest to visit another location. The local government had received funds to build a primary school in each sub-district but they ended up leaving many of the schools vacant since the parents could not pay for their children to attend the school. Our Venerable Brother borrowed one of these primary schools for our Understanding and Love Program. (“We’ll eventually borrow all of them,” he said with a charismatic smile.) I was surprised to discover that these public schools include just a few relatively big rooms and no toilets or sinks! (The tea plants surrounding these schools must grow well with the natural fertilizers.)

The children at this location were also of the K-ho ethnic group. Their clothes were discolored and many did not even have socks or hats. It was cold and windy, but they all sat on a thin straw mat on a cement floor; there were no toys and no decorations in the room. The children simply sat still and silent.

I placed a small girl on my lap. The teacher said to me, “The father of that child died last year in a vehicle accident. Her mother is only 22 years old and she has to take care of two children by herself. They are very poor.” The child was 17 months old, but when I pulled her up, she could stand for only a few seconds before she sat back down. Yet her face was beautiful and calm like a full moon, and her eyes opened wide.

Little Zen Masters

Again and again at each location, Therese and I were deeply struck by the children’s demeanor—and by their eyes. They were quiet and still, but their bodies and minds were not flaccid or lethargic. Their eyes were wide open and calm, yet penetrating. I saw them as little Zen masters in meditation, sitting in ease and acceptance.

We went to three more locations that afternoon. When we arrived at the last school we had tea with the two teachers and an elderly woman whose granddaughter attended our school. The tea was particularly strong and fragrant. The women told me that most of the tea plantations in this area belonged to Taiwanese owners who lived in Bao Loc with their families. The local workers were allowed to use only the old tea leaves for drinking (called chè); the young tea leaves were harvested for exports (called trà). I said to them that I must be drinking trà, and the elderly woman smiled in embarrassment, saying, “Well, it’s a special occasion that the Venerable and you are here, so I went to the tea garden back there and took a few young leaves.” She smiled.

Spiritual Nourishment

I asked the teachers if they were tired after taking care of the children from 6:30 a.m. to 5:00 p.m., Monday to Saturday. They smiled, a smile of kindness, acceptance, and endurance.

“How do you nourish yourselves?” I asked them.

“We go to Prajna temple and the monks and nuns teach us how to take care of the children and of ourselves,” one teacher told us.

“How does the practice help you?”

“I learn to bring joy to other people. I don’t get so upset anymore. If I didn’t hear the children’s voices for a few days, I would miss them!” she replied.

On our visits to the schools we discovered the importance of spirituality. “Hunger and poverty is one kind of suffering,” said our Venerable Abbot. “Yet, the lack of spirituality is a greater suffering. The people in these areas are very poor, but they live their lives with honesty and joy because they have a spiritual practice. If not, their lives would be much darker,” he said.

The Beauty of Interbeing

Towards the end of our time together, our Venerable Brother slowly looked at each of our faces. Then he turned to speak to the four social worker brothers, “Well, do you have any last thing to say to sister Therese? Tomorrow, on our way to Saigon together, we will be practicing silence and hand gestures!” Everyone laughs wholeheartedly because they know I will not be in the car with them to translate.

On the way to the car, Therese and I reached out to embrace one another. I follow mindfully my in-breaths and out-breaths, as I feel concretely Therese’s presence in my arms. We have shared meaningful and beautiful moments together. I am keenly aware that I may never see her again, yet our lives are forever intertwined.

And the eyes of the children, they will always remind us to reflect deeper into our path and to remember. Remember. Remember.