By Mitchell Ratner and Jerry Braza

Early in the morning we leave our Beijing hotel on five deluxe buses: 150 of us from 16 countries, traveling with Thich Nhat Hanh and 30 monks and nuns from Plum Village and the Green Mountain Dharma Center. The major urban arteries are crowded with new cars, bicycles, and tricycles hauling goods and people. Commercial buildings on the major boulevard display billboards for Western products such as Pepsi Cola and Marlboro cigarettes.

By Mitchell Ratner and Jerry Braza

Early in the morning we leave our Beijing hotel on five deluxe buses: 150 of us from 16 countries, traveling with Thich Nhat Hanh and 30 monks and nuns from Plum Village and the Green Mountain Dharma Center. The major urban arteries are crowded with new cars, bicycles, and tricycles hauling goods and people. Commercial buildings on the major boulevard display billboards for Western products such as Pepsi Cola and Marlboro cigarettes. Thirty minutes later, the buses turn into an older neighborhood where they barely have room to maneuver in the narrow streets. Branches scrape our windows.

The buses stop, and as we were instructed, the monastics disembark first. We put on our ao trangs, the long grey temple robes traditionally worn in Vietnam. Tiep Hien members put their brown coats on over their ao trangs. We pass through the temple gates and enter the compound of the Ling Guang Temple. The city buildings and noise push their way to the gates of this compound, but the guardian figures, huge incense burners, trees, courtyards, and temple halls inside evoke a different world. We move through courtyards and shrine rooms. Thay and the monks walk ahead; we form a long procession behind. On both sides of us are lay people who have come to greet us and hear Thay speak. They bow with palms together, often saying "Amitofo, Amitofo, " "Homage to Amitaba Buddha." Many hand us prayer bead bracelets and pictures of Buddhas. Later we learn that the proper etiquette is for us to place our palms together in a lotus and keep walking mindfully, as Thay does when he enters a Dharma hall, but in this first temple visit, we try to return every smile, every bow, and yet keep moving.

Some minutes later we catch up with the head of the procession. Thay and the monastics are met by the abbot and monks of this temple. Together they enter a large Buddha hall and stand in front of three huge gilded Buddhas, the Buddhas of the past, present, and future. We file in behind the monks. Some of the Chinese lay people come behind us. Others stand in the courtyard or crowd the doors, attempting to get a better view. The abbot, representing the Buddhist Association of China, greets us warmly, noting that it is the first time the association has sponsored a visiting delegation from 16 countries. Thay then leads the delegation in touching the earth three times, honoring the buddhas and the abbot. The abbot, Thay explains, represents not only the Buddhists of today's China but also all the teachers from many generations: "We are here in China because Buddhism has been treasured and nurtured here for twenty centuries. The Buddhist culture in China is like refreshing water that lies deep in the Earth. The world suffers. If we practice deeply, we can make the water of Buddhism available to others."

So began May 15, 1999, our first full day of a journey to honor the Chinese roots of the Buddhist tradition that we have learned through the teachings and presence of Thich Nhat Hanh. During the next twenty days, we traveled from Beijing south to Guangzhou, visiting temples, monasteries, monastic training institutes, and historical sites in ten cities. Along the way we were deeply inspired by a sense of reverence from just being where fabled events occurred. We walked in Nan Jing, where in 225 A.D. the Vietnamese-trained monk Tang Hoi brought Buddhism to the Wu Empire and ordained the first Buddhist monks in China. We visited the Guangxio Temple in Guangzhou established by the legendary Bodhidharma, who brought the Dharma to the Emperor of the Liang dynasty in 525 A.D. and established the line of Chinese Patriarchs. In the mountains east of Guangzhou, we walked the ground of Nan Hua Temple, established in the seventh century by Hui-Neng, the Sixth Patriarch, the enlightened kitchen worker who received the Fifth Patriarch's bowl and robe and was then forced to flee south.

Four hours by bus from Beijing we stayed three nights in Bai Lin Temple, established in the ninth century by Chao-Chou, one of the many Dharma descendants of the Sixth Patriarch, whose insight lives on in numerous Zen teaching stories. A short bus ride from the Bai Lin Temple is the Big Buddha Temple where Lin Chi taught. A contemporary of Chao-Chou, he grounded Ch'an Buddhism in appreciation of daily life: "The miracle is not to walk on water, it is to walk on this earth." Sister Chan Khong noted that for us, as students of Thich Nhat Hanh, Lin Chi is our spiritual "Grandfather Monk." The Lin Chi lineage was brought to Vietnam in the 12th century and Thich Nhat Hanh is of the 42nd generation of Dharma teachers in this tradition.

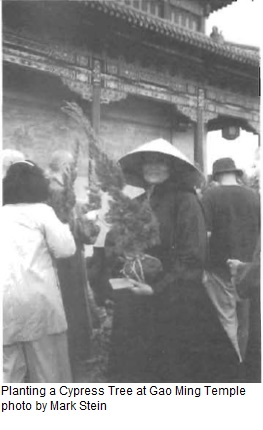

Our longest stay was six nights at the Gao Ming Ch'an Monastery, situated on the Grand Canal, an hour's drive from the city of Yang Zhou. For several centuries, Gao Ming has been a center for the preservation and transmission of Ch'an Buddhism. During the Cultural Revolution it was essentially destroyed. The monks were scattered and the main buildings were converted to a silk weaving factory. In the 1980s, after the Cultural Revolution, the monks were able to reclaim their land and in the past fifteen years they have rebuilt and rejuvenated the monastery. Much of the financial support comes from the overseas Chinese Buddhist community, many of whose teachers were trained at Gao Ming.

Although we traveled and visited historic sites, our visit was not simply a tour. It was a pilgrimage and a cultural exchange. The tone was set the first night when Thay explained that we were in China not as individuals, but as a family, as a Sangha, a traveling community of practitioners. Our practice would be the Plum Village practice of maintaining a mindful state of being in all of our activities, supported by our conscious breathing, mindful eating, and mindful walking. "Whether we walk in a railroad station, Buddhist temple, or on the Great Wall, our practice is the same. We walk with mindfulness."

During our journey, the lessons came in many forms. Sangha building began even before the trip. Via the internet, participants helped each other prepare for the trip and shared information, concerns, and encouragement. In response to the unrest caused by the bombing of the Chinese embassy in Belgrade, Thay said not to worry. "Our Chinese ancestors will protect us as we practice peacefully and joyfully together." Along the way, the teachings of compassion and love helped us face the physical and emotional challenges of traveling in China with a large group. Often we returned to Thay's counsel, "When one is not grateful, one suffers." When we were mindful, each step, each meal, and each encounter offered an opportunity to be grateful. Although Thay gave numerous Dharma talks, for many of us the most memorable teachings came when we were with Thay in an airport lounge or encountered him late at night in the shadows of a monastery courtyard. He was always modeling the practice for us, silently encouraging us to slow down and enjoy this very moment.

In addition to deepening our knowledge and practice, the pilgrimage was an opportunity to share the Plum Village practice with Chinese practitioners. Knowledge of Thay's teaching is slowly growing in China—a Chinese translation of Old Path, White Clouds was published to coincide with our visit. When the abbots of the temples and monasteries introduced Thay or thanked him, they often acknowledged his rare ability to translate Buddhist insights into clear images and practical actions that modern women and men can understand and follow. Thay frequently returned to the theme of making the practice joyful, especially in his talks to young Chinese monastics.

At Bai Lin and Gao Ming Monasteries, we joined with the monks in their Ch'an practice, which was diiferent from Plum Village practice. We sat on elevated benches, facing Buddha statues in the middle of the meditation hall. Even in warm weather, the monks tightly wrapped blankets around their legs, to hold in spiritual energy. A sitting was forty to sixty minutes (traditionally, one incense stick). Walking meditation was fast to very fast. In Bai Lin, the walking paths in the meditation hall were arranged in concentric circles—the inner circle being for the speediest, the outer for the slow walkers, usually the ill and old. In Gao Ming, there was no option, we all walked fast. The fast pace was intended to assist one in concentrating on walking rather than the thoughts that arise.

The underlying orientation to the meditation practice was also different. In Plum Village, practitioners are encouraged to be ever mindful of their breath and develop insight into the interrelated nature of life. Chinese monks in the Ch'an tradition usually work with a koan, especially the practice of always asking themselves "Who is?" "Who is sitting? Who is eating? Who is walking? Who is invoking the Buddha's name?" As both Thay and the abbots of the monasteries pointed out, however, the differences are outer forms only. They share a common essence established by the Buddha in India, by the Chinese Patriarchs, and by Lin Chi, to whom the abbots and Thay all trace their Dharma heritage.

During an informal conversation, someone mentioned to Thay that it was too bad certain high monks were not able to hear his Dharma talk. Thay replied that it didn't matter, they didn't need to hear the talks. If we practiced well, all they needed to do was look at us. This was true of both the visitors and the hosts. Communication, respect, and admiration flowed both ways, even when no words could be exchanged. Many in our group were especially taken by the kindness, dignified bearing, and bright smile of Master De Lin, the 85-year-old abbot of Gao Ming Monastery. Thay said of him: "His heart is full of compassion, and yet he is very firm."

Throughout the trip, we were touched by the simple generosities offered by Chinese monastics and lay people: a smile, a picture, a waiting bowl of fruit, a heartfelt bow, or simple guidance. Collectively, we were brought to grateful tears when it was announced during our leave-taking banquet at Gao Ming Monastery that the staff who cleaned our rooms, prepared our meals, served us, and cleaned up afterwards were all volunteers who had given up their vacation time and left their families to make our stay comfortable.

When Master De Lin gave us a tour of Gao Ming's new Buddha hall, much of which he himself had designed, he mentioned that behind the Buddha was a bas-relief of Kwan Yin, the Bodhisattva of compassion, relieving many beings of their suffering. He then suggested that perhaps the best way to relieve suffering in the world is to become friends. In many ways, he was summing up our journey. As a traveling sangha we had lived and practiced together and become closer as friends. And as communities of Buddhist practice from Plum Village and from the temples, monasteries, and training institutes of China, we had shared from our hearts, learned from each other, and established bonds of respect and friendship.

Mitchell Ratner, True Mirror of Wisdom, practices with the Washington Mindfulness Community and the Still Water Mindfulness Practice Center in Takoma Park, Maryland. Jerry Braza, True Great Response, practices with the River Sangha in Salem, Oregon.