By Alan Cutter

I am now at a place where I can begin to talk about what the war has meant to me. I am facing the hurt and regret, and learning to understand how they have affected my family and my relationships with other people. Through owning up to the bad choices I made, I can value having made the best choices I could when there were no “good” choices. Before, when I spoke about my experiences,

By Alan Cutter

I am now at a place where I can begin to talk about what the war has meant to me. I am facing the hurt and regret, and learning to understand how they have affected my family and my relationships with other people. Through owning up to the bad choices I made, I can value having made the best choices I could when there were no "good" choices. Before, when I spoke about my experiences, I would become so emotional, even with my wife, that I could not speak. Either the sadness, or anger, or something else would take my voice away. A wall existed for me and I was resigned to living with it. Now, I have received permission to speak, to break that wall of silence imposed by society and by my own fears and anxieties.

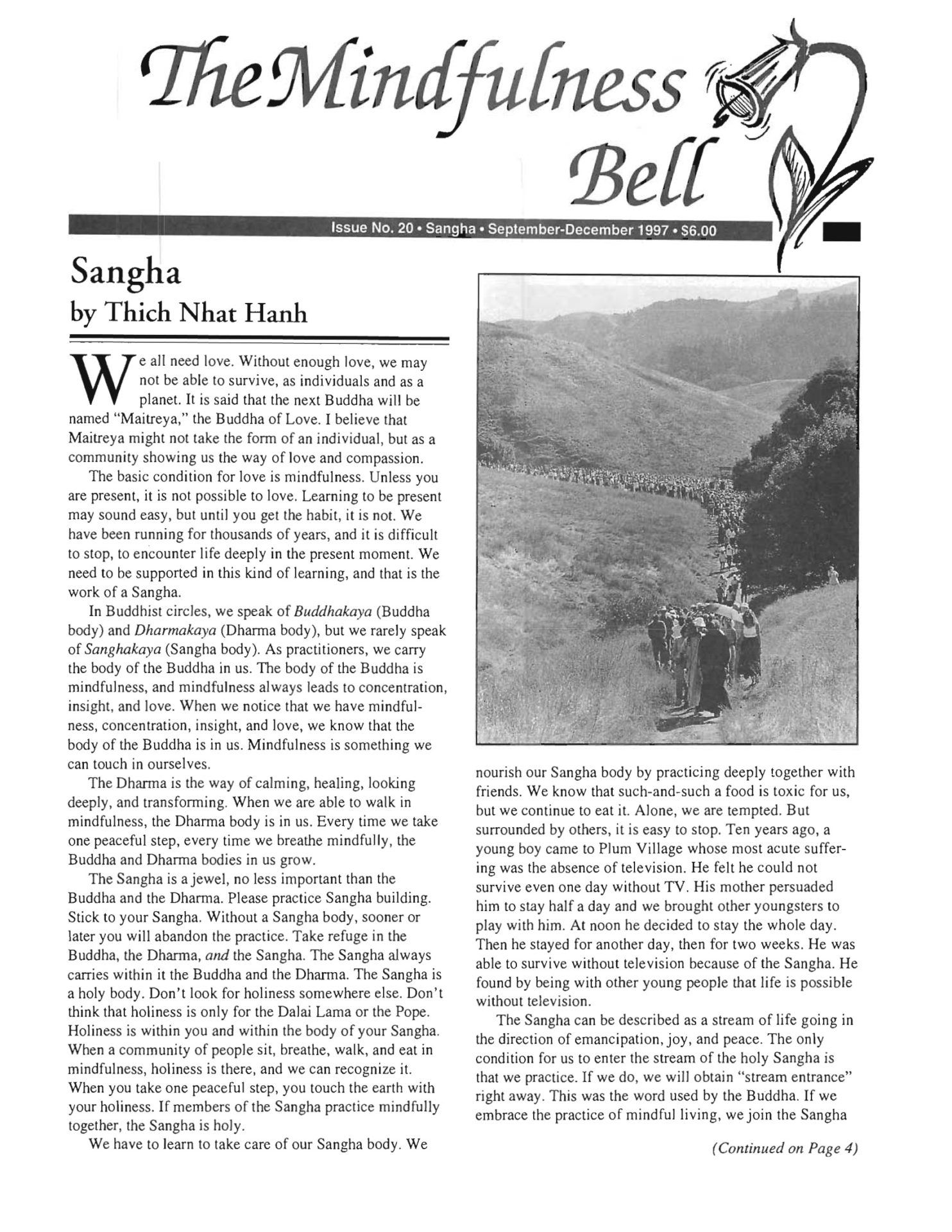

It began on a trip to California, when some of us drove to Half Moon Bay to look at the Pacific Ocean. I thought if I could look out across the ocean towards Southeast Asia, I might somehow say goodbye to what I had left behind. But I could not do it, for there was too much left unsaid and unfmished. I was trying to do it all alone, just as I had to do in Vietnam.

A few days later, our group was visited by Arnie Kotler and Therese Fitzgerald from the Community of Mindful Living. They brought Claude Thomas with them, a vet from Boston who had experience with Thich Nhat Hanh's teachings. Arnie and Therese led us in breathing exercises designed to help people focus on living in the present moment. We did sitting meditations and a walking meditation. During these meditation periods, Therese held a small bronze bell which she would occasionally strike with a baton. It was, she explained, "a device to remind us to focus on our breathing, on what we are doing right now, on smiling, on being peace."

After these exercises, Claude told his story. Before he did so, he admitted he was scared to speak. He had been a door gunner on a chopper, celebrating both his 18th and 19th birthdays in Vietnam, and had a powerful story of failed relationships, loneliness, fear, and homelessness. He talked of boobytraps and sudden death, turkey shoots, hatred, revenge, and great pain. As he spoke, every so often he would begin to get visibly caught up in his emotions and start to lose control. When this happened, Therese would strike the bell and Claude would stop, take two or three deep breaths to refocus, and then calmly continue with his story. As I watched, I found myself wishing I had something, anything, that would enable me to do the same thing.

After his story, Claude shared something he had learned from Thich Nhat Hanh-that it is necessary and important for vets to break the walls of silence around our experiences. We must find some method for telling the truth of war and conflict. For Claude, the sound of the bell gave him the permission he needed to speak.

I told Claude how moving it had been to watch his struggle and how I noticed that with the sound of the bell, he was able to refocus and continue. In a moment of unintended truth, I said I wished I had something like that, a bell, that would help me break my own wall of silence. Claude looked at me and said, ''The sound of the bell is yours. You want it, now you have it and you can speak!" As the impact of his words hit me, I sat in my chair and stared at him, one hand holding my glasses, the other empty. Then Therese was beside me, putting the bell and the baton in my empty hand, and saying, "I believe in making things concrete-the bell is yours."

The bell is not perfect-it has blemishes and little scratches, but its sound is true and clear. To me, it is a gift from the Vietnamese community. Now I carry the sound of the bell in my head and I can speak about my war experiences without getting caught in the strong emotions. It is not easy, but it is real. I was trying so hard to break the wall of silence by myself, but what I needed couldn't be accomplished alone. As much as I needed to speak, I also needed people on the other end, willing to listen.

I don't know where you are in your journey, but I know how easy it is to slide into old habits-to get discouraged, to be satisfied with a little bit of progress and give up hoping that there is more. Cherish your progress, but do not ever give up. The next bit may come unexpectedly. Look for it, be open to it, brother. In hope and love, Alan

Alan Cutter is a Presbyterian minister living in Duluth, Minnesota.