By Anne Rogal Winiker

Because the Jewish year is based upon an ancient lunar calendar, Jewish holidays are never on the same date from one year to the next. Thus, my nonrefundable plane tickets were already purchased when I realized that our most sacred holidays overlapped the time period of “The Heart of the Buddha,” the September retreat in Plum Village. I felt conflicted, but stuck to my decision to spend Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur far from home.

By Anne Rogal Winiker

Because the Jewish year is based upon an ancient lunar calendar, Jewish holidays are never on the same date from one year to the next. Thus, my nonrefundable plane tickets were already purchased when I realized that our most sacred holidays overlapped the time period of "The Heart of the Buddha," the September retreat in Plum Village. I felt conflicted, but stuck to my decision to spend Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur far from home. My rationale that "spiritual work is spiritual work" did not appease my family. As I departed, my younger brother hugged me and hissed into my ear, "Have a safe trip, happy holidays, and don't ever do this again!"

The day after my arrival at Plum Village was also three days before the first of these holy celebrations. There was a group of Jewish retreatants, and written recognition from Thay about the importance of this time "for our Jewish brothers and sisters." But how would we celebrate without rabbi, services, or synagogue? The Jewish group numbered about 40, and most of us were now sitting in a big circle by the linden tree, trying to figure out how to create our own ceremonies.

"I feel like crying," one woman said. "I can't believe nothing has been organized."

"I'd like to develop something accentuating Buddhist themes."

"We have twenty-one days of Buddhist themes. I want a Jewish service."

"We need a bell. Someone please ring a bell."

"Maybe we should just go find a synagogue in Bordeaux."

"Can we talk about process before content?"

"My name is Shalom," said Shalom. She extended her hands, and one by one we connected our circle, closing our eyes, breathing, and finding ourselves united, after all.

The days passed, and a small group worked to .combine strongly-held philosophies and opinions, ceremonial objects and writings, and favorite songs and traditions. My sense of mission expanded abruptly when Ruby, a non-Jew, insisted that the celebrations should be offered to everyone at the retreat. "What a wonderful opportunity to experience our true interbeing," she said. Startled, I realized the image I held of our Jewish group celebrating unobtrusively in some quiet corner. To share the significance of this time with non-Jews was unprecedented in my life.

As the holidays approached, we prepared our texts so that an "outsider" would be able to understand them. We made announcements and public invitations. When we gathered by the bamboo grove to rehearse our music, we. were joined by new people, strangers to us and to the Jewish traditions. A large circle of singers formed, standing and swaying as our ancestors have done in worship through the ages. The newcomers approached the unfamiliar Hebrew words and haunting melodies with incredible zeal. Emanuele, a non-Jewish friend from Italy, said, "I feel as if I have always known this music."

The 60-strong German Sangha loomed large for me. They circled us, clearly wanting to participate. Eulysia, gentle and self-effacing, had joined our first planning group. "I'm not a Jew, I don ' t know if it's all right for me to be here, may I help with something?" I felt the sincerity of her intention, and a pain behind it. Why did I also feel a sense of annoyance, as if I wondered, "What could you do anyway?" The next day two handsome, blond men approached us, politely offering, " May we share with you?" in German accents. As they sat down, I felt an intangible sense of threat, and could not get the phrase "perfect Aryan specimens" out of my mind. Several of my new Jewish friends were children of concentration camp survivors. I wondered if the religious services could somehow serve as a vehicle for German-Jewish reconciliation. But I didn't know how to reconcile these visceral feelings that came from a time before many of us were even born.

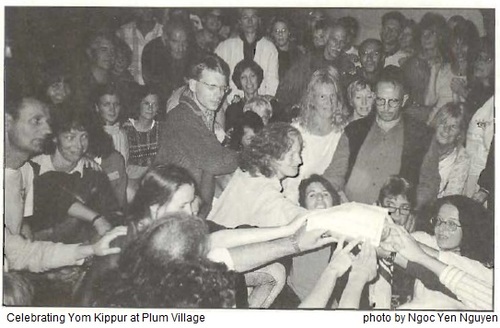

Friday evening arrived, bringing the Sabbath and Erev Rosh Hashanah, the eve of the New Year. To my amazement, perhaps 200 people gathered in the large meditation hall of the Upper Hamlet. Thay was there. The room glowed with warm candlelight, illuminating the flowers, fruit offerings, and rose-colored Buddha statue. Together, we sang the beautiful melodies. People's arms extended around their neighbors. Together, we rose to call out the Shema, the "watchword of the Jewish faith," affirming the Oneness of God. Stretching our arms to the sky, we affirmed the oneness of us all. We blessed bread and fed pieces to each other, saying, "May you never be hungry." And we recited the Shehechianu, a prayer for blessing anything new. We were blessing not only the New Year, but also this new Sangha of Jews and non-Jews celebrating at a Buddhist retreat. As the service ended, Nel , a friend from Holland, rushed up to me. "I want to convert!" she exclaimed.

"Tashlich" is the New Year's Day ceremony symbolizing throwing away one's sins. Thay led the Sangha on a mindful walk to the little pond in the Lower Hamlet. We had been instructed to gather small sticks along the way. At the water's edge we stood silently for a few moments, then threw the twigs into the water and called out aspects of ourselves we'd like to cast away for the new year. Soft voices filled the air: "My greed, my impatience, my lack of involvement, my anger. .. " We were told to imagine these attributes transformed into our aspirations for the coming year. Suddenly, miraculously, the sticks sprouted wings! Brown dragonflies arose from the pond and took flight.

As we turned to go back, I felt a hand on my shoulder. It was Andreas, one of the "Aryan duo." In that profound moment I felt a warm recognition. We bowed, smiled, and embraced in a meditation hug. Then with silent accord we took each other by the hand and began to walk. I became terribly self-conscious: "I don't know this man. German. Jew. It's hot. Why is he walking so slowly? My shoulders feel so tense." Eventually, mind and body relaxed, hands remaining gently linked. We were going slower and slower. Each pace took me deeper into my mind. I saw myself led on a death march into a concentration camp. But here was a German friend, and he was coming with me. I was an African child, leading a blind grandfather on the long walk from the river to our hut. I was the first of a long line of Jews, and he of Germans, with our ancestors and the generations to come stretched out behind, walking, walking. I was myself, and a student of mindfulness, taking one slow step after another, no attainment, no path, no destination. Thay's gatha from walking meditation the previous day returned to me. I practiced it, linking silent words to my breathing and my footsteps: "Andreas, Andreas, I am here; Anne, Anne, I am here," bringing myself with him into the present moment even as, absurdly, a loud megaphone from some nearby auto racetrack blasted noisy commentary across the fields. Present moment, wonderful moment.

Trust blossomed, and friendship without discrimination was born. The stereotyped German and Jewish concepts fell from me as gently as the sticks had fallen into the pond. Later after we had talked, we brought the idea of a German-Jewish dialogue back to our friends. This idea bore fruit. On two separate evenings, about 35 people from both groups met to share their historical wounds, fears, shame, guilt, and mistrust. Gentle mediation by the visiting Japanese Zen Roshi and the respectful setting of shared mindfulness brought healing for many.

After the ten "Days of A we" separating the two holidays had passed, we gathered again to celebrate the eve of the solemn Day of Atonement. The service opened with a poignant and powerful song, Kol Nidre. This ancient prayer absolves us of vows that could not be kept from the previous year, and symbolizes cleansing and purifying our failures. Jacqueline, a violinist whose Jewish parents raised her as a non-Jew, said that she had "lived, eaten, and breathed" the Kol Nidre music for two weeks at her tent site. Now she played it for the ceremony, and her violin cried and soared. We could feel the pain and joy of her Jewish spirit, finding its voice after a very long sleep.

On Yom Kippur, Jews and non-Jews gathered in the Transformation Hall throughout the entire day, fasting, praying, singing, breathing, and sharing together. The ceremonies were profound: meditations on forgiveness; recollecting our dead; casting rose petals into bowls of water as we shared our memories, traditional Hebrew prayers and song; a writing exercise, beginning with the words, "I remember" ; a symbolic purification ritual, washing of the hands; the prayer for healing, preceded by calling aloud the names of our loved ones who were ill. Then it was sundown, and we heard the thrilling, ancient sound of the shofar, the ram's horn. "May you have a good year!" We all embraced, went through the food lines together, and broke our fast in hungry and eager mindfulness. Over and over the words kept turning in my mind: "We are the heart of the Buddha."

Anne Rogal Winiker is a wife, mother, musician, and physician living in Boston, Massachusetts. She practices with the Community of Interbeing